Degrees of Success

College grads making high marks on the World Cup

Above: World Slalom Champion Laurence St-Germain. University of Vermont photo.

The 2023 Alpine World Championships in Courchevel/Meribel, France, served up the usual mix of big-event excitement, with medals from favorites like World Cup overall champs Mikaela Shiffrin and Marco Odermatt, and surprises like unheralded super G winner James Cameron of Canada.

The excitement culminated on the final weekend in the slalom events. On the men’s side, AJ Ginnis (formerly of the U.S. Ski Team) nabbed silver—the first-ever winter sports medal for Greece— while Canadian Laurence St-Germain unseated Shiffrin to claim slalom gold. Both took unlikely paths to the top, detouring off their national teams and back to the World Cup through NCAA skiing.

Overall, these most recent World Championships featured 18 athletes who represented eight U.S. schools and their NCAA ski teams. The U.S. Ski Team alone featured six former NCAA athletes, including St-Germain’s former University of Vermont (UVM) teammate Paula Moltzan, who led Team USA to gold in the team parallel event. Canada’s entire slalom squad consisted of former or current NCAA athletes. What started out as a few racers juggling college studies, NCAA racing and World Cup skiing has now led to a World Cup start list populated by alumni of American universities.

College skiers are present throughout the World Cup development spectrum. They include athletes like Ginnis, St-Germain and Moltzan, all of whom were dropped from their national teams after performance dips; like Ali Nullmeyer, Amelia Smart, Katie Hensien and Tanguy Nef, who all started their World Cup careers as NCAA skiers; and like Jett Seymour and Justin Alkier, who used college skiing to develop World Cup–level strength and speed. Their success underscores how long the journey is to make it in ski racing and the viability of college racing as a vehicle to get there.

On the Nordic side, it’s always been customary for US athletes to work their way up via college skiing. And in the early days of Alpine ski racing, U.S. Olympic teams were populated with college athletes from schools like Dartmouth, UVM and Middlebury in the East, the University of Colorado and the University of Denver in the West. (For an in-depth look at the evolution of NCAA skiing, see “Foreign Relations,” Skiing History, July-August 2017). But with the advent of the World Cup and increased professionalization of national teams, the collegiate circuit became less attractive to aspiring racers. By 1980 there were no collegiate athletes on the U.S. Alpine Olympic Team.

College Comeback

College skiing came back as a development vehicle when NCAA races became FIS sanctioned. Following the lead of Western colleges, Dartmouth held the East’s first FIS university race in 1995, leading to what is now a fully FIS carnival circuit. As FIS-level racing legitimized NCAA events, the level of competition rose. More college athletes were motivated to compete on the NorAm circuit, where minimum FIS-point penalties are on offer, as well as World Cup start spots for the overall winner plus the top two athletes in each discipline according to the final NorAm standings.

The first American to fully exploit the revived college opportunity was David Chodounsky. A walk-on to the Dartmouth team, Chodounsky leveraged four years in a stable program into World Cup momentum. In 2009, a year after graduating, he made the U.S. Ski Team and later became the top male American slalom skier until his retirement in 2018.

Chodounsky debuted on the World Cup the same season as Norwegian Leif Kristian Haugen, then a sophomore at the University of Denver (DU). When Canadian Trevor Philp foreran the 2010 Vancouver Olympics as a junior racer, he noticed Haugen racing for Norway and also for DU. In 2012 Philp, too, started at DU and when faced with the choice between the national team and college, he chose both. Three years later, Erik Read followed Philp, establishing what would become a well-worn path for Canadians.

On the women’s side, Hedda Berntsen was a three-time All American skier for Middlebury before winning a world championship medal for Norway in 2001. Canada’s Elli Terwiel (2014 Olympian) and Norway’s Kristina Riis-Johannessen (2017 world champ medalist) pushed the pace at UVM, ushering in the parallel rise of St-Germain and Moltzan. Both earned starts for their countries in the Killington World Cup while college racing, opening their paths to the top of the ski-racing world.

Longer Careers, Tighter Budgets

The average age of male and female top competitors has steadily risen, as has the age of retirement. The U.S. Ski Team’s biggest stars of the 1980s retired before age 30. Today, the average age of the top 30 men on the World Cup is 28 in technical events and 31 in speed. On the women’s side, that average is 27 in tech and 28 in speed, with many veterans skiing deep into their 30s. U.S. stars like Lindsey Vonn and Bode Miller retired at ages 34 and 40, respectively. With more veterans hanging around at the top, it’s even tougher for young athletes to break in. The process takes time and money.

The longer glide path of development has coincided with tighter budgets throughout the industry, decreased support from national teams and vastly increased expenses for aspiring racers. Gone are the days when talented teenagers enjoyed free equipment and national team funding. Post–high school gap year programs can cost as much as tuition at an elite university but without the education. College programs, on the other hand, offer intellectual and career development, a vibrant social life, athletic scholarships for some and, for all, funding for in-season ski racing expenses. All of this, along with less funding at home, steadily lured foreign athletes across the pond to take advantage of this uniquely American asset and boost the level of competition.

Developing Trend

Americans, too, started opting for college as a development strategy. In 2014, faced with a $14,000 bill to ski for the national team or a full four-year scholarship to DU, Jett Seymour chose to follow Philp’s example and do both. Katie Hensien said yes to both as well, graduating from DU in four years. Each of them picked up an NCAA title while transitioning to the World Cup. Said Seymour in an interview with Ski Racing: “College was exactly what I needed to help me mature and realize there is stuff outside of my little bubble of ski racing.”

Collegiate skiing can be a way to regroup, to ease into World Cup racing or to extend the development runway. “It takes the pressure off, and you look at the long game rather than just the short game,” says Alkier. The 2021 Middlebury grad secured both a World Cup start and a spot on the Canadian team for 2023–24. “It was always a dream of mine to race in NCAA,” says Smart, who looked up to athletes like Terwiel and Read as a youngster. “I never had really thought of just doing the World Cup path.”

Returning to Speed

NCAA athletes have also found success on the World Cup speed circuit. 2016 Junior World Downhill Champion Erik Arvidsson was a promising junior racer on the U.S. Ski Team but felt burnt out. He decided to change course and attend Middlebury. It was a risky move for a speed skier because NCAA racing only includes slalom and GS. Arvidsson recalls, “I was worried that I was choosing my life path at the time, at the age of 20.”

Instead, being part of a tight team rekindled his love for racing. Classes pushed him academically while teammates like Alkier and Tim Gavett pushed him athletically. By the time Arvidsson graduated in 2021, he had scored an eighth place in the World Cup Finals. He ended last season with a 14th-place finish in Aspen’s World Cup super G, where MSU senior Riley Seger finished 10th. After earning her degree in 2021 Dartmouth skier Tricia Mangan reclaimed a spot on the World Cup speed tour and the U.S. Ski Team.

Private Teams Take up Slack

Also helping athletes choose college racing is the rise of private, multinational teams that compete on the World Cup. Among them is Global Racing, a collection of 14 athletes who compete for 10 nations. Many of them missed the small window to earn a spot in their national teams’ development programs but are now at prime age for the World Cup. The Americans in the group—George Steffey, Brian McLaughlin and Patrick Kenney—all earned World Cup starts last season.

Gavett, who now holds a physics degree from Middlebury, will be gunning for World Cup starts with Global next season. He points out that the commitment and effort it takes to pursue ski racing at the highest level through and beyond college is self-selecting. “The amount of people who are willing to do that is quite small,” says Gavett.

The Challenges

The hurdles are significant and go well beyond skiing fast and studying hard. NCAA rules prohibit schools from training together in the off-season, which for skiing means from April to November. As Arvidsson explains, “The only people who make it [on the World Cup] out of college are the people who are incredibly savvy and fortunate on being able to organize summer training and who have access to good coaches and really good equipment and do a lot outside of the programs on their own.” He heaps credit on Gavett’s parents, who deployed their expertise and European network to facilitate more than 40 days of high-level off-season training for Arvidsson, Alkier, Gavett and Nullmeyer.

While Eastern athletes benefit from icy training surfaces and proximity to European glaciers and race venues, Western athletes have access to early-season snow. One reason Smart chose DU was because of the six-week winter break. “It’s kind of a perfect time for me to be able to go to Europe, do some World Cups and not miss a ton of school,” she says.

The Sooner, the Better

The satisfaction and support that comes with being part of a collaborative team—where everyone is invested in each other’s success—tops the list of collegiate skiing’s advantages. Of his Middlebury teammates Alkier says, “I don’t think I would have had success without them.” Smart notes that on the Canadian national team, “We all know what it felt like to be part of a college team, and we all want to recreate that and engender that within our team.”

Ginnis adds that it’s important to be realistic about a dangerous sport that only pays well at the very, very top. “If you’re not a top-30 athlete yet, college racing is the best solid return on your investment you can make as a skier.”

The biggest advantage college skiing offers is simply time. Even though he rocketed through the ranks, won a junior world medal and ascended to the World Cup early, Ginnis, who raced briefly for Dartmouth, thinks a solid dose of college skiing earlier in his career would have been a better path. “I lacked a certain maturity, especially when it came to racing,” he says. If he had a do-over? “I would have definitely gone to school when I was 18, 19 years old and raced a couple of years, at least, in college.”

He points out that the majority of skiers who start racing World Cup early on take forever to break through to consistent second runs, getting beaten down in the process. “The older and more mature you are when you start racing full time on the World Cup, the better it is,” says Ginnis. Also, the more established you are on the circuit, the more difficult it is to toggle back and forth to college skiing; in the beginning, however, the variety of pace and atmosphere can ease the transition to the big leagues.

Overwhelmingly, the advice World Cup grads offer to younger athletes who want to go to college is to go earlier rather than later. Athletes are heeding that advice. American Cooper Puckett entered Dartmouth as a freshman while on the U.S. Ski Team’s D squad. As a sophomore, he raced for Dartmouth as well.

“It was a pretty scary decision to make,” recalls Puckett, who sought advice from Ginnis. “He helped me completely visualize it and map it out.” Puckett says watching Ginnis win his silver medal “the most inspiring thing ever.” In addition to competing in his third Alpine Junior World Championships, Puckett earned a spot on Dartmouth’s 2023 NCAA Championship team and improved his ranking enough to advance to the U.S. C team.

Graduate School

St-Germain’s Instagram profile reads: “Alpine ski racer, Olympian, World Champion 2023, full-time student.” After earning her degree in computer science from UVM, she is pursuing a second undergraduate degree in biomedical engineering. Smart, meanwhile, graduated with a double major in environmental science and computer science in 2021. Then, with teammates St-Germain and Nullmeyer engaged in their studies, she got bored on the road. “I decided that I know I can do school and ski so I might as well keep going,” says Smart.

Read completed the Canadian Securities Course last summer. Ginnis puts his econ chops to work daily managing his own team—from sponsorships to training to staff. Nef used his computer science major for an internship with Amazon, and Alkier feeds his interest in finance by researching investments during his down time. This summer, Arvidsson fit in an internship at BlackRock Asset Management. For him, a college degree means that when he’s done with skiing, he’ll have more options.

The security of a college degree is priceless and is also often misrepresented. Gavett, for instance, doesn’t look at his physics degree as a Plan B in case ski racing doesn’t work out. “It’s not a backup,” he explains. “It’s a future when you’re done ski racing.”

Regular contributor Edie Thys Morgan wrote about Mikaela Shiffrin closing in on Ingemar Stenmark’s all-time World Cup wins record in the March-April 2023 issue.

Current NCAA College Grads on the World Cup

Here’s an unofficial scorecard of NCAA grads competing in the World Cup, including birth year, name, nationality, years racing in the NCAA; college, year of graduation and degree.

’91 Erik Read, Canada, NCAA 2015–17; University of Denver ’17 Business

’93 Brian McLaughlin, U.S., NCAA 2015–18; Dartmouth ’18 Engineering

’94 AJ Ginnis, U.S./Greece, NCAA 2020; Dartmouth ’22 Economics

’96 Tanguy Nef, Switzerland, NCAA 2017–20; Dartmouth ’20 Computer Science

’96 Erik Arvidsson, U.S., NCAA 2018-21; Middlebury ’21 History

’97 Riley Seger, Canada, 2019–22; Montana State University ’23 Business Finance

’97 Simon Fournier, Canada, NCAA 2019–22; University of Denver ’23 Business Finance

’97 Patrick Kenney, U.S., NCAA 2018–20; University of New Hampshire ’21 Economics

’98 Justin Alkier, U.S., NCAA 2019–22; Middlebury ’22 Economics

’94 Laurence St-Germain, Canada, 2015–19; University of Vermont ’19 Computer Science

’96 Roni Remme, Canada/Germany, NCAA 2016–20; University of Utah ’20 Psychology

’97 Tricia Mangan, U.S., NCAA 2019–20; Dartmouth ’21 Engineering

’98 Amelia Smart, Canada, NCAA 2018–21; University of Denver ’21 Double Major Environmental Science/Computer Science

’99 Katie Hensien, U.S., NCAA 2019–22; University of Denver ’22 Marketing and Entrepreneurship

’98 Ali Nullmeyer, U.S., NCAA 2020–23; Middlebury ’23 Economics

Paused after junior year

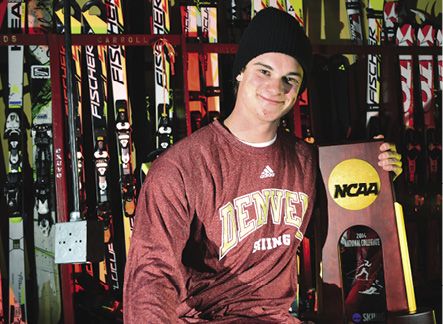

’98 Jett Seymour, U.S., 2018–20; University of Denver, International Business and Finance

’94 Paula Moltzan, U.S., 2017–19; University of Vermont, Biology