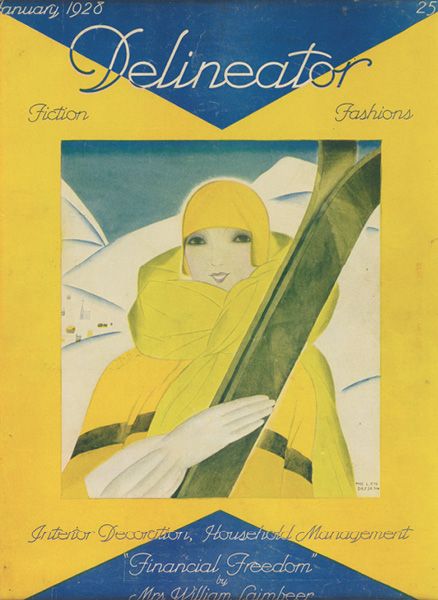

Ski Art: Helen Dryden (1882-1972)

Helen Dryden’s artistic life split into three directions, all held together by Art Deco. As a youngster, Dryden showed artistic talent and was noted in Philadelphia papers like the Public Ledger and the Press. Her training was in landscape painting but she soon gave that up to draw women’s fashions. In 1909 she moved to New York City. She had success with her first cover for Vogue in 1910 and remained on the payroll for 13 years. During this Art Deco period her covers conveyed the good life, especially for women. Dryden also created covers for Home and Garden and Vanity Fair as well as designed costumes for Broadway productions and the Ballet Russe.

It is unclear why she stopped working for Vogue. During her second period, the mid- to late 1920s, Dryden designed patterns for wallpapers, textiles and hats, plus lamps and small items for Revere in copper and brass. As she embraced industrial design for the home, she joined the woman’s magazine Delineator. Then, with larger things in mind, she worked for the Studebaker automobile company.

The world of cars was defined by men into the 1920s, but just about the time of the stock market crash in 1929, it was becoming obvious that women also influenced the family’s choice of car. Dryden realized this and made changes to the interior design of Studebakers—not just the leather look and instrument panels, but also small details like the ash containers. By 1930, she had become a household name, and advertisements mentioned “the gifted Helen Dryden” and her “impeccable good taste.” She was reportedly the highest-paid American woman artist, earning $100,000. But all was not money; she also exhibited in the Brooklyn Museum.

Between 1940 and 1956, nothing is known of Dryden. In 1956 her subsistence welfare check was reduced to $30. She had run through her fortune, become unhinged and, in 1966, was

institutionalized in a New York state hospital, where she died in October 1972. It was a sad end to America’s “first lady of fashion.”