Short Turns: Cigarettes and Skiing

A history of early sportswashing.

As Italian ace Zeno Colo stood in the giant slalom starting gate at the 1950 FIS World Championship races in Aspen, he was smoking a cigarette right up until the countdown started, when he flicked it casually into the snow. No one thought much about it at the time. Today, when watching the film of the event, nearly every audience laughs and hoots.

Colo was a flamboyant and elite competitor (Olympic and World Championship gold medalist), and his Aspen starting-gate ritual was just one more sign of his nonchalant coolness, reinforced when he won the race. At that time in Western culture, smoking cigarettes was one of the most fashionable things you could do: sexy movie stars smoked (on and off-screen), models lit up and so did famous athletes. Smoking had become almost as much a staple of American life as drinking. In 1964, the peak year for smoking in the U.S., 42 percent of Americans smoked. Children even sucked on candy cigarettes to look as grownup as their parents.

So when full-page cigarette ads in prominent national publications began to feature skiing, it was a sign that the sport had gone mainstream. It also was a sign that tobacco manufacturers understood a match made in heaven: use skiing’s healthy, hip vibe to sell their products.

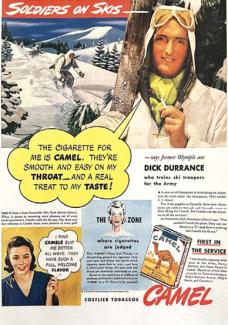

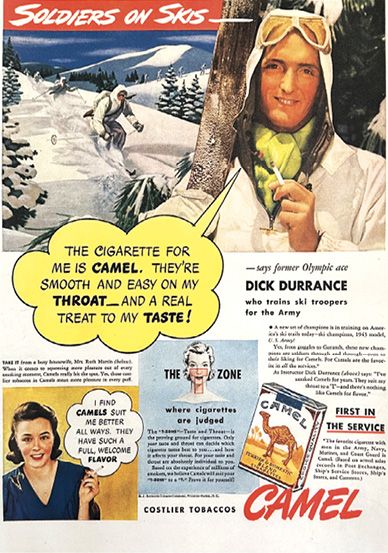

A 1943 Camel cigarette ad included photos of World War II ski troops as it touted cigarettes’ popularity in the various military services, where mini-packs were included in soldier’s K-rations. When the legendary American skier Dick Durrance appeared in a different Camel ad that ran in Colliers in the early 1940s, he was attired in military snow-camouflage gear (see illustrationi, top of page). Though Durrance helped train paratroopers, he never served in the 10th Mountain Division -- instead he worked as a test-flight photographer for Boeing's B-29 project.

If Mikaela Shiffrin started hawking Marlboros tomorrow, there would be a massive uproar, of course. Attitudes toward smoking started to shift in the mid-1950s, when several epidemiology studies, in both the U.S. and Great Britain, began to clarify the link between smoking and illnesses such as lung cancer. The landmark 1964 U.S. Surgeon General’s report, which showed a direct link between smoking and life-threatening diseases, sealed the deal.

Following the damning U.S. Surgeon General's report,

magazine cigarette ads continued to use skiing as a backdrop, both to convey smoking’s sexiness and as a subliminal smoke screen to obscure its health hazards. The ads were an early example of what is now called “sportswashing,” using athletics to improve public image by redirecting attention away from questionable ethics or behavior.

The term has been around since the mid-2010s, and Amnesty International has been attributed with adding it to the modern marketing lexicon. However, it wasn’t until recently, as countries and corporations financed major sports leagues and athletic events, attempting to improve their international reputations, that the word stuck. For example, in 2021, Saudi Arabia, known for violating human rights, underwrote LIV, a new professional world golf tour, to the tune of several billion dollars.

The practice is not new. Perhaps the most famous early example of sportswashing was when Nazi Germany hosted the 1936 Olympics—both the Winter and Summer Games. The international spotlight that’s focused on the Olympics is a natural fit for sportswashing, with recent examples that feature skiing arguably including Russia’s 2014 Sochi Winter Games and China’s 2022 Beijing Winter Games.

After the 1964 surgeon general’s report, skiing was still frequently featured in tobacco ads. Remarkably, that sportswashing trend increased over the next few decades. In 1971, tobacco ads were banned from broadcast media. After being removed from the airwaves, tobacco companies quickly pivoted huge advertising budgets to print, with skiing prominently featured in some of the ads.

The magazine advertising landscape shifted dramatically in 1998, when a legal agreement between tobacco companies and state attorneys general included a restriction on tobacco ads in magazines that had significant youth readership. Currently, no formal ban exists on all print tobacco ads, but by the mid-2000s, they had mostly disappeared from mainstream magazines.

Despite the concerns of many, others feel like the sportswashing label is really just virtue-signaling. It’s hard to criticize any athlete for taking the money, this argument goes. Blame the system, not the player, whether it’s golfer Jon Rahm going to LIV for north of $300 million; Tadej Pogačar getting more than 8 million Euros annually cycling for UAE Team Emirates; or Dick Durrance for whatever he got at a time when ski racers weren’t making much of anything.

If Mikaela Shiffrin started hawking Marlboros tomorrow, there would be a massive uproar, of course.

Snapshots in Time

Snapshots in Time

1956 The New Way to Ski

During the past year or more, a violent controversy has been raging in European ski circles—in the press, in ski schools, in organized skiing. The subject of this dispute is “Wedeln” (vay-duhn), a word which we will henceforth adopt into our SKI vocabulary without qualifying quotation marks. Wedeln is the new running style developed by racers and now almost universally practiced by them and other topnotch skiers. — Brooks Dodge, “Ski the New Way” (SKI Magazine, October 1956)

1963 Will the Skiing Boom Continue?

PARIS —Still another major aerial cable lift has opened in the Alps, this one at Chamonix two days ago. While skiers rub their hands with glee, the financiers worry whether this new lift (and so many others not much older) will catch on. Will the boom in skiing continue indefinitely? The new lift, called the Lognon, rises off Argentiere near Chamonix. It starts at 4,050 and climbs to 6,368 feet. — Robert Daley, “New Lift makes Some Think It Is Time to Stop” (New York Times, February 19, 1963)

1976 What Did He Prove?

To ski down Everest. The notion is at once magnificent and ridiculous, brave and silly. To spend $3 million, to muster an expedition of 850 men and 27 tons of equipment, to sacrifice six lives in order to photograph a man skiing down a mountain for four minutes . . . what a peculiar and wonderful thing we have here in the human ego. What did he prove? Not that he could ski down Everest, perhaps, but at least that he would try. Does his attempt place him in the history books next to Hillary, or Evel Knievel? We leave the film not knowing. Perhaps the title—“The Man Who Skied Down Everest”—provides a clue. No matter how long Miura lives, how far he travels, how many people he meets, he will always be an easy man to introduce at a party. — Roger Ebert “The Man Who Skied Down Everest” (Chicago Sun-Times, September 23, 1976)

1982 Are You a Gourmet or Gourmand Skier?

Among skiers, there are gourmets and there are gourmands. The gourmets select a resort as carefully as they would the wine for an important occasion. Once they’ve found a ski area to their liking, they return to it year after year, learning its ways and savoring its idiosyncrasies. The gourmands prefer to gobble up mountain after mountain, priding themselves on the number of slopes they can consume in a season. — Clifford May, “At Large on Skis in Colorado” (New York Times, March 21, 1982)

2002 Extreme Over-Xposure

Blame Scot Schmidt. Or the misguided corporate-American marketing machine. Or ourselves. But the world “extreme”—which once had something to do with danger—is now used to market everything from razors to Right Guard deodorant to really good ice cream sundaes. (Note to Madison Avenue marketing managers: Make “X” bigger than the other letters.) — “Extreme Influence” (Skiing, December 2002)

2025 Every Skier’s Dream

The precipitous decline catches up with everyone. Even with modern skis that make it so much easier. Even with attention to fitness being greater now than ever before. It doesn’t matter if you have good genes, a relentless conditioning regime, have avoided injuries that nag you as you age, or you’re just plain lucky—father time catches us all. — Lee Cohen, “Becoming an Old Geezer Should be Every Skier’s Dream.” (Powder Photo Annual, Summer 2025)