Short Turns: The Final Splash

For nearly 100 years, skiers have closed the season into the drink.

As the story goes, in spring 1928, Cliff White and Cyril Paris, Banff Ski Club pioneers and experienced Alpinists, chanced upon a large snow-melt pond far below them in Banff, Alberta’s backcountry. They challenged each other to see who could skim farthest across the meltwater on skis.There’s no record of who won, but, voilà—a soggy end-of-ski-season ritual was born.

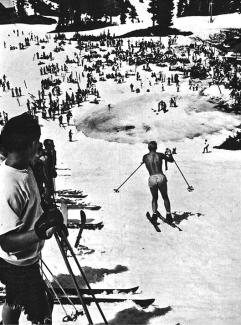

(Photo top: Mt. Baker, Washington, held its Slush Cup beginning in the early 1950s. Mt Baker photo)

Taking advantage of this colorful origin story, Banff Sunshine resort will celebrate its “96-ish” Slush Cup in late May, on the final day of the season. The resort touts it as the oldest pond-skimming event in North America. Flexing its own bragging rights, Sugarbush, Vermont, claims to be the oldest official event in the U.S., though the resort can’t pin down an exact starting date. It also claims to offer participant sAmerica’s longest stretch of open water at 120 feet.

Perhaps the most influential of the original pond-skimming celebrationsinthe U.S. may be the Mt. Baker Slush Cup, started in the early 1950s in Washington State. An early adopter of the end-of-season format, Mt. Baker, however, credits its pond-skimming fame to movie maestro Warren Miller, who said he was invited to the resort in 1954 to film the new event. “Thecombination of high-altitude, hot July sun, high blood-alcohol content and wobbly legs offered some fantastic, never-before-seen crashes for my next year’s feature-length ski film audiences,” Miller recalled in a 2015 Tahoe Guide newspaper column. Pond-skimming antics became a staple of Miller’s oeuvre, with the filmmaker claiming his 1950s coverage ignited a movement.

Vail, Colorado, winks as it touts its event as the World Championships of Pond Skimming. Whitefish Mountain Resort in Montan aawards $1,500 in cash across a multitude of categories. In California, Palisade Tahoe’s Cushing Crossing, now in its 33rd year and one of the more iconic skims in the U.S., features a proper pond and has become so popular that it now limits the event to 50 participants.

Big Sky, Montana, annually held one of the more innovative pond skims in the country prior to Covid. Every year, the creative manmade ponds changed format, with sometimes two of them side by side or end to end, and with kickers and rails, drawing hundreds of rowdy fans and participants. After a few years off, pond skimming returnedt o Big Sky this spring to close the ski season.

Colorado’s Arapahoe Basin, always in tune to counter programming, offers its unofficial and weather-dependent pond skimming across “Lake Reveal,” typically in June. Melting snow and local topography unite, under the proper conditions, to create a natural small pond near the top of the resort. No official spectators. No entry fees. No prizes. The pond is available at any time, to anyone who is up to the challenge.

The unique and notorious Ski Splash at Snowmass, Colorado, began in 1970 and persisted until 1984 before the plug was pulled over insurance issues. The event had a kicker on the slope above whart was then the El Dorado Hotel's outdoor swimming pool. Instead of skimming across it, the often scantily-clad participants did their aerials and landed in the pool. Hopefully. But not always. Hence the cancellation.

Skiing's spring bacchanalia vibe is global, of course. Pond skimming translates to water sliding in Europe, with the attendant components, however, consistently similar. Participants costume up or strip down and strive to take skis, snowboards, ski-bikes, cardboard airplanes, patrol toboggans or, occasionally, a full-body Styrofoam Eiffel Tower costume or a wrap-around Titanic ship across a frequently purpose-built pond at the end of a slope. Expect to see sharks and pirates and beach-themed attire. Moses often parts the sea, and Jesus "walks" at a brisk pace. Think soap-box derby on snow. The event typically includes live music, rivers of beverages, sponsor banners, loaner life jackets, paramedics and hundreds, often thousands, of revelers.

Switzerland's Engelberg Titlis resort was once famous for its mineral water, so it takes water sliding seriously. The resort holds multiple rounds to determine the winner, with the pond's approach slope shortened after each round, gradually reducing water-planing speed.

In the annual Defi Foly contest at La Clusaz, France, skiers don't zip across a man-made slush hole -- they take on an actual lake, where the ice is usually only partially broken up by the second half of April. Helmets and life jackets are mandatory, and participants start on a steep hill above the lake, tuck all the way onto the water and try to glide across 525 feet. The half-dozen rescue boats stay busy all day. In 2011, Frenchman Philippe Troubat, a Freeride World Tour competitor, cleared 509 feet, which he claims as an unofficial world record. For pond-skimming purists, however, his achievement might require an asterisk in the record book: He rode a monoski.