Pioneers: The Bill Healy Story

The summit was his opus.

Skiing resurrected many a Western near-ghost town during the middle years of the 20th century. Aspen. Alta. Crested Butte. Park City. Telluride. Beginning in the late 1950s, lift-served skiing on Mt. Bachelor helped transform Bend from a fading central-Oregon timber town into the multi-sport recreational hub it is today. And, although it might be a stretch to call Bill Healy the godfather of modern Bend, he was the irrepressible force behind Mt. Bachelor’s birth as a destination and an engine of the regional economy.

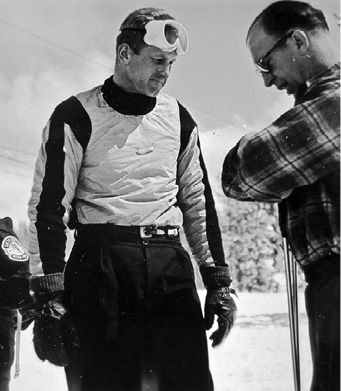

Photo top: Bill Healy enlisted in the 10th Mountain Division right out of high school.

He had help, of course. Scandinavian lumberjacks and mill workers flocked to Bend once the railroad arrived in 1911 to harvest the vast ponderosa pine forests east of the Cascades crest. They brought with them their love of skiing and, in 1927, founded the Skyliners Club, which carved a ski jump, slalom hill and log lodge out of the forest up Tumalo Creek west of Bend. (See “The Northwest Legacy of the Skjersaa Family,” Skiing History, January-February 2025.) The Skyliners hill was limited, though, and no one in town could miss, on clear days, the sight of Bachelor Butte, a 9,056-foot high, dormant stratovolcano on the horizon 22 miles west-southwest of downtown.

The Skyliners saw it and staged races there, beginning in 1935. Bend native Gene Gillis saw it and hiked the summit to ski the Alpine snowfields many times. Gillis was a local ski hero, multisport letterman in high school, gymnast, diver, football star at the University of Oregon and shoe-in for the 1948 U.S. Olympic ski team before he shattered his ankle training downhill right before the Games. In the early 1950s, while coaching ski racers in Sun Valley, Gillis was lured home to Bend to coach the Skyliners, and it was then that he and Healy began their fruitful relationship.

Healy was born in 1924, in Portland, and as a teenager became an avid skier and racer on Mt. Hood, where two of the state’s earliest ski areas, Ski Bowl and Timberline, had opened in the 1920s and ’30s. Fresh out of high school in 1943, Healy enlisted in the newly forming 10th Mountain Division. According to his son Cameron Healy, he taught skiing to recruits on Cooper Hill at Camp Hale in Colorado. As a private first class radioman with the 86th Infantry Regiment, he participated in the storied assault on Riva Ridge and was awarded a Bronze Star for his involvement in the brutal fighting around Lake Garda in the final days of the war in Italy.

Following Germany’s surrender, a group of 10th Mountain skiers stationed in the Carnic Alps, defending what would become the Italian/Yugoslav border, reunited for a long-imagined ski race on Mount Mangart. Using gear appropriated from Axis warehouses, they climbed Mangart’s 8,927-foot height and set a racecourse in the vestigial spring snow. The winner, appropriately, was Sgt. Walter Prager, Dartmouth ski team coach and former world downhill champion. Not far down the list of finishers, in 10th place, was one William Healy.

Following the war, with his wife, Bobbie, and the first of their four children, Healy moved to Bend to manage his family’s downtown furniture store. He soon joined the Skyliners Club and by the mid-1950s was elected president. The club vice-president was Don Peters, the U.S. Forest Service recreation officer for the Deschutes National Forest, soon to become one of Healy’s most important allies.

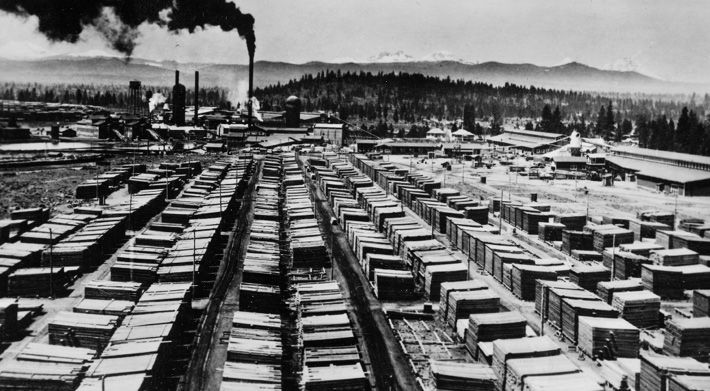

At this time, Bend’s timber industry was in steep decline. For the first couple of decades after the railroad arrived, Bend’s mills supplied more pine lumber to the nation’s building boom than any other producers—something like 500 million board feet annually. But it didn’t last. Over-cutting the trees and the mills’ declining profits sent Bend’s population plummeting, to below 12,000 people. One of the two giant mills on either side of the Deschutes River had closed, and the other was on its last legs.

What to do? In 1957 the answer coalesced in the perfect blend of talents: Healy’s irresistible smiling Irish drive, Gillis’ skiing connections and Peters' pull with the forest service. Plus a bit of bad luck turned good. The Skyliners’ Tumalo Creek lodge burned in January of that winter. In February Gillis led a party, including Healy and Peters, on an exploratory ski of what was then called Bachelor Butte. And, in astonishingly short time (“We may have bent a few rules,” Healy said, with a twinkle in his eye, according to biographer Peggy Chessman Lucas), they had formed Mt. Bachelor, Inc., with Healy as president. By late 1958, the Bachelor Butte ski area would open for lift-skiing business.

To raise the $100,000 they needed, Healy began peddling shares—4,000 of them at $25 each—from the back room of the furniture store. There were four initial major investors in addition to Healy: a prominent local doctor; an insurance salesman; a life-long skier from Minneapolis who had come to Bend on his honeymoon in 1939 and never left; and Oscar Murray, a friend of Healy’s and the owner of a heavy equipment company who offered to build the mile-long road to Bachelor’s base and scrape out a parking lot for his block of shares.

Gillis asked his friend Christian Pravda to come over and help lay out trails and lift lines. The two had met racing in Europe in the years following the St. Moritz Olympics, and Pravda, a two-time Olympian for Austria and the 1954 world downhill champion, agreed. Gillis also encouraged Healy to invest not just in the two planned rope tows, but also in a Poma lift to whisk skiers higher on the mountain. Company founder Jean Pomagalski himself came over from France to supervise the lift’s installation.

The Poma cost $60,000, taking a great chunk out of the budget. But the ski area was ready for opening day, December 19, 1958. The forest service issued only a one-year temporary permit. There was a small shed-roofed base lodge and pit toilets. The water had to be trucked up from Bend. Healy sold the $1.25 daily lift tickets out of his station wagon. And 800 people showed up to ski. Bachelor was a success from day one.

That first season the lifts ran only on weekends and holidays, but enough skiers visited that the corporation showed a year-end profit of something north of $5,000. They came mostly from Bend and surrounding central Oregon communities, but also, to the surprise of skeptics in the forest service and Bend’s own chamber of commerce, from Portland and the Willamette Valley population centers of Eugene and Salem—despite a one-way drive of up to four or more hours.

If they stayed overnight, they slept in Bend. They ate and drank in Bend. And they skied on the mountain. With the brief exception of a year or two renting overnight rooms in the day lodge (an experiment that Healy admitted was a mistake), Mt. Bachelor has never had or seriously campaigned for on-slope accommodations. (The permit land is 100 percent U.S. Forest Service.) And thus the initial, and ongoing, symbiotic relationship: town and mountain.

Skeptics, Healy included, had long worried that destination skiers would be hesitant to travel to ski a “butte”—it didn’t sound impressive enough—and petitioned to have the name changed from Bachelor Butte to Mt. Bachelor. Traditionalists in the map name-changing world balked but eventually relented, and in 1983 Mt. Bachelor gained official recognition.

By then the ski area had two day lodges and half a dozen chairlifts, including the nation’s second (after Breckenridge) Doppelmayr detachable to the volcano’s summit. Also by then, Healy had been diagnosed with an “ALS-like” neuromuscular disease.

During the resort’s early decades, he had skied every day, exploring as he looked for new runs and lift locations. His son Tom Healy says you could hear him yodeling all over the mountain. But by 1980 his balance and coordination were off, and speaking was becoming more difficult. Nonetheless, he kept working. “The summit was his opus,” Tom says. “It kept him alive for another 12 years.”

From the beginning Healy wanted to get a lift to the top, to be able to ski all 360 degrees off the cone and extend Bachelor’s vertical to a legitimate 3,000 feet. On nice spring days guests were hauled to the summit in an open-air stretch Tucker snowcat Healy called the Monster. But that was just a taste; a chairlift was the goal.

It didn’t come without opposition.

Environmental groups in Bend argued that a summit lift terminal and a road cut into the treeless Alpine terrain would be unacceptable eyesores. But Healy’s enthusiasm prevailed. Friends said he’d kissed the Blarney Stone and was, therefore, blessed with “the power of sweet, persuasive, wheedling eloquence.” In the end, with much seat-of-the-pants engineering bravado, the lift was built without cutting a road through the lava rock. Today, a life-size bronze statue of Healy stands in front of the mid-mountain Pine Marten Lodge, pointing east toward the summit lift.

Even as his disabilities grew, Healy kept charging ahead. Tom recalls lifting his dad from his wheelchair into the driver’s seat of a Tucker cat and then jumping quickly off the treads as Bill gunned the engine and sped off on his daily mountain inspections. One time he drove the cat into a fumarole and had to be rescued. Another time he scraped the bark off two big western hemlocks, having misjudged his ability to squeeze the cat between them.

Healy was irrepressible despite soon losing all ability to speak. (He referred to this, in weekly staff meetings, as his “giggle and drool” period.) To communicate, he typed on a computer keyboard, which then projected words on the office wall. He retained his humor to the end of what he called his “hoof and mouth disease.” Healy was driven to work every day until his final week, in October 1993.

Bend was booming again, and showed its appreciation for Healy all over town. There is the bronze on the mountain, installed in 1997. The newest bridge crossing the Deschutes is the Healy Bridge.

Healy was also a big supporter of the U.S. Biathlon Team, and the National Guard armory in Bend is named for him. The Skyliners Club, where it all began, evolved into the nonprofit Mount Bachelor Sports Education Foundation, which named its new state-of-the-art facility the Bill Healy Training Center.

The Bend Bulletin’s editor said, in a documentary commemorating Healy’s 100th birthday in 2024: “Bill Healy turned snow from a nuisance to a lifeblood.” The documentary is subtitled A Man Who Loved a Mountain.

Longtime ski writer Peter Shelton is an occasional contributor to the magazine. His latest book is Tracks in the Snow from Western Eye Press. He lives in Bend, Oregon.

The Sale That Wasn’t

Mt. Bachelor, Inc., took pride in its local ownership and its interlocking fortunes with the city of Bend. It has had, until now, just one ownership change, and that one was controversial.

In 1998, an offer to buy the resort came from Utah-based Powdr. All of the original investors, including Bill Healy, had died or moved on. Many on the board, including Healy’s family, thought it was time to sell. Others bridled at the thought of “outside ownership.” In the end, Powdr’s offer was accepted.

As one of Powdr’s stable of nine ski areas in the U.S. and Canada, Mt. Bachelor continued to expand and upgrade. But in August 2024, Powdr announced it was putting the mountain up for sale. (It had recently sold Killington ski resort, its flagship Vermont property.) Almost immediately, central Oregon skier/snowboarders Chris Porter and Dan Cochrane announced the formation of Mt. Bachelor Community, Inc., and its intention to submit a bid to buy the resort. They made no bones about the fact they wanted to “save not just the resort but their way of life” from what they called “the titans of the industry.” Their grassroots effort garnered the attention of the New York Times, which published a lengthy piece titled, “Revenge of the Ski Bums,” which, in turn, generated more attention.

Now, in April 2025, after nearly eight months of silence from the sellers, came the surprise announcement that Powdr had reversed course: “There are numerous factors in evaluating a sale. After consideration of all facts and circumstances, Powdr has decided to retain ownership of Mt. Bachelor, indefinitely.”

In response, a representative for Mt. Bachelor Community, Inc,. told local media that his organization felt heard by Powdr and is hoping to “see if there’s any kind of partnership opportunity that could evolve … down the road.” —P.S.