Equipment: The Missing Link

In 1970, Lange’s SuperComp equipped 16 World Cup teams. It was never sold to the public.

In the mid-1960s leather ski boots were first reinforced with internal fiberglass plates (see “Le Trappeur Elite,” Skiing History, July-August 2021) and then replaced by boots made entirely of polyurethane and other tough plastics. With these stiffer boots, racers were better able to hold an edge on hard, icy snow, executing turns previously impossible to make. The downside was that plastic didn’t break in to comfortably cradle a skier’s foot.

Photo top: SuperComp cuff was 25mm higher than the Comp cuff.

For Alpine racers, pain was a small price to pay for winning. The first generation of Lange boots quickly won a loyal following in the racing community, “Lange bang” notwithstanding. Among the first to try the plastic Lange was Canadian Rod Hebron, who rocked Langes (and Dynamic VR7 skis) at the Silver Belt race in Sugar Bowl, California, in the spring of 1965. The following year, Bob Lange brought half a dozen pairs of boots to Portillo for the FIS World Championships, and Suzy Chaffee used them there to take fourth in the downhill, her career best in international racing.

By the 1968 Olympics, dozens of racers used Langes. Nancy Greene won gold in GS and combined, and silver in slalom, in in the boots, and Heini Messner won bronze in GS and combined. Lange soon supplied no fewer than 16 national teams.

In fact, from 1967 to 1970, Lange was the dominant boot supplier to race teams worldwide. Meanwhile, racers trying to learn the French avalement technique needed something even newer. To take full advantage of the new technique, and the new stiff-tailed slalom skis, they wanted better rearward support from their boots. By 1970 racers on all boot brands took to stuffing tongue depressors down the backs of their boots or riveting on aluminum or plastic extensions, looking for more height and support for “jet turns.”

The Missing Link: The Lange SuperComp

None of this was lost on the product managers at Lange. The company’s entire marketing identity depended on racing success. In the early summer of 1970, Dave Jacobs, VP of Lange, former coach of the Canadian team and designer of the original Lange Comp, teamed up with newly hired Chris Hanson to design a new upper cuff to fit on the existing Comp lower shell. They planned to make the new cuff about 20 millimeters higher all the way around, not only for improved edge control but also to create a higher, integrated rear “spoiler” to support jet-turn action. Finally, to relieve the Lange bang issue, the top of the tongue would be supported by a wider buckle strap in front.

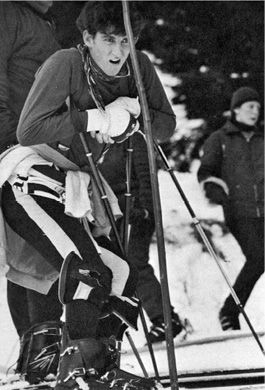

Prototypes of this boot, dubbed the SuperComp, were tested by Canadian and U.S. team members in the 1970 summer and fall camps. Going into the 1971 World Cup season, racers could choose between the original Comp and the new SuperComp. Technical specialists like Tyler and Terry Palmer, Bobby Cochran, Gustavo Thoeni and David Zwilling chose the SuperComp, while downhillers like Billy Kidd and Bernhard Russi stuck with the original version, which offered more ankle flex for superior gliding.

The SuperComp was a success because it gave racers the ability to control the ski from any position: center, front or back. In the past, skiers would ride a ski not unlike a surfboard, being careful to always stay in a balanced position. With the improved leverage offered by the SuperComp, a racer could dominate the ski and edge angle. This new style of boot changed ski technique forever.

Commercialization

Why was this successful racer boot never introduced commercially? As successful as the SuperComp was during the 1970–71 World Cup season, it also tended to tear apart over time. All that wonderful leverage overloaded the cuff’s and spoiler’s riveted connections to the lower shell. With strong skiers, boots broke at the side and back rivet holes in less than one season.

Lange management, still reeling from the 1969–70 Lange-Flo debacle of liners developing messy leaks, decided that for the 1971–72 season it would quickly cobble up a design with the same basic dimensions but molded as a single piece, with no hinges. The new one-piece design was never accepted by racers. This commercial version turned out to be a disaster because when flexed, it bulged around the ankle, eliminating precise control. After a single season the “stovepipe” Comp was superseded by the 1972–73 Banshee; it had the same basic dimensions but used a two-piece, overlapping shell design molded in bright reddish orange and a removable inner boot. The Banshee would not look out of place in a product line-up today.

Only several hundred SuperComps were built, and they were only available to national team members. Yet as one of the first designs to establish the foundational elements of modern ski boots, it is a missing link between old and modern boot technology.

Scott Boyer skied in Lange SuperComps while attending the University of Utah, then worked for Lange as a racer service technician. He went on to develop boots and other products for skiing, motorcycling and mountain biking.

Convergent Evolution

Other factories were thinking along similar lines. At Nordica, Sven Coomer devised the leather Sapporo (1969) and, later, the one-piece plastic Olympic (1971) and two-piece Grand Prix (1972). Caber began work on what would become the Alfa. For 1971, San Marco introduced a two-piece hinged shell so high it used six buckles and featured miniature jackscrews to adjust both forward lean and side-hinge canting. Martin Strolz marketed a version with his own inner boot. — Seth Masia