Andermatt Reborn

How a sleepy Swiss resort underwent development on steroids.

Andermatt needed a financial partner. ASO photo.

Switzerland’s Andermatt was among the earliest Alpine resorts. (The name, which translates to “at the meadow,” refers to the town’s location, near Gotthard Pass.) Well-to-do adventurers began summering here at the height of the Romantic era in the early 19th century, and skiing arrived with Swiss army trainees around 1890. Historic but sleepy for much of its existence, Andermatt went into fast-forward mode in 2005 with the arrival of an Egyptian billionaire, who invested $1.4 billion to create one of the most luxurious resorts in the Alps. In 2022, Vail Resorts upped the ante, buying a 55 percent stake in the development.

This is a tale with as many turns as a slalom course.

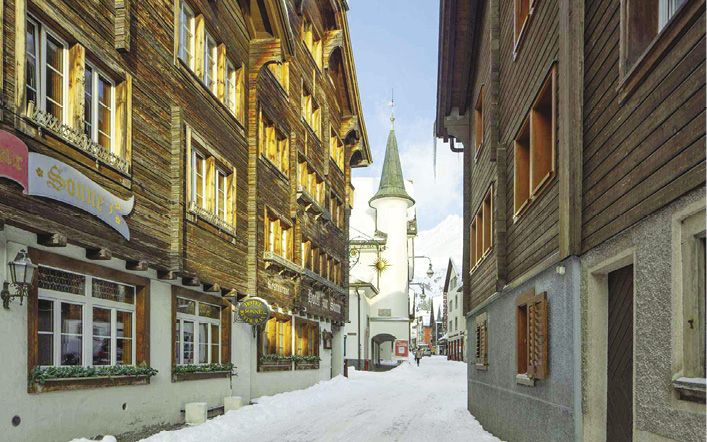

Set at 4,737 feet elevation (1,440 meters) in a dramatic valley with steep mountains on all sides, Andermatt is a charming town of venerable Alpine architecture, quaint shops and onion-domed churches. You are, indeed, in the land of Heidi.

It’s also surrounded by impressive slopes, with two main ski areas: Gemsstock, where intermediate and expert skiers can find challenging runs and a vertical drop of nearly 5,000 feet, and the gentler Nätschen/Oberalp area on the Gütsch, where easier slopes await on the sunnier side of the resort.

At first glance, it’s a very nice and well-situated resort, without the name recognition of Zermatt or St. Moritz. But then you spot the sleekly modern new hotels and apartments at the edge of town, with cutting-edge Alpine architecture that blends in with the centuries-old neighbors. Due to restrictive zoning, those new buildings are a rare sight in any Swiss ski resort, and they tell a remarkable story of revitalization, unfolding by the day.

Queen Victoria and the Swiss Army

Andermatt sits in the Urseren Valley and is part of the Saint-Gotthard Massif. It is essentially the center of the Alps, where north-south and east-west meet in Switzerland. This is also the headwaters of the Rhône River, flowing westward and south toward the Mediterranean. A few miles in the other direction, the Rhine River emerges and heads north and west to empty into the North Sea. The snowstorms of the central Alps also tend to converge here, making it one of the best powder spots in the country.

Three of Switzerland’s most significant mountain passes also meet here—the Furka, the Gotthard and the Oberalp—making the area an important crossroads even before Roman times. Archaeologists note traces of temporary Neolithic camps (around 4000 B.C.E.), but the earliest documented evidence of permanent settlement was by the Walsers, a Germanic tribe, in the second century C.E. They gave their name to the region and its modern inhabitants.

The main barrier to north-south communication across the region was the raging Reuss River. The first Teufelsbrücke (Devil’s Bridge) across the torrent was built in 1220, opening a mule-train track to Italy. Gradual improvements to the road eventually allowed the passage of horse-drawn coaches, beginning around 1775. The strategic bridge, located about half a mile north of Andermatt’s town center, was the object of a bloody battle in 1799 between Napoleon’s troops and detachments of the allied Russian and Austrian armies. But Napoleon then won the battle for Zurich, which rendered meaningless the Russian success at Andermatt.

The town provided hostel services to the mail coaches crossing Gotthard Pass daily. The very first Baedeker guidebook, published in 1854, listed hiking trails, bridle paths, coach roads and inns in the region. Soon enough, luxurious hotels went up. Queen Victoria came to stay at the Grand Hotel Bellevue, which opened in 1872. That year, work began on a rail tunnel under Gotthard Pass. When it opened in 1882, trans-Alpine traffic bypassed Andermatt and the tourist trade cratered.

tourists as a ski lift from the valley. ASO,

However, Andermatt’s enviable strategic position kept it valuable for military purposes. The Swiss army established a major base here in the late 19th century, intended to be a wartime headquarters if the country were invaded. This required construction of a rail spur in 1914, which also enabled skiers to schuss about two miles and 1,200 vertical feet down the valley and ride the train back up. Andermatt got its first proper ski lift in 1937.

Throughout the mid-20th century, middle-class Swiss families favored the resort for holidays, even as wealthier international skiers went to better-known slopes like Gstaad, Zermatt and St. Moritz. The first cable car to the Gurschenfirn glacier on top of Gemsstock opened in 1964, allowing for summer skiing (since 2005, that glacier has been wrapped in a protective cloth to slow melting).

Around the same time, Hollywood came knocking, and scenes from Goldfinger were filmed here, including the famous car chase on the Furka Pass, with Sean Connery as James Bond driving his classic Aston Martin.

That brush with fame aside, Andermatt remained a quiet ski town in the middle of the country, a parochial vacation area that offered untouched powder stashes for savvy ski bums. It was like any other quaint Swiss town, though this one happened to have lift-serviced skiing at its doorstep. It was otherwise notable as a quick stop on the famous Glacier Express train that runs 180 miles between Zermatt and St. Moritz.

By the turn of the 21st century, the town was languishing, and the ski area was losing money. In 2004, the army base was downgraded to a training center, and the town lost most of its military revenue. The region faced economic crisis.

A Fast-Paced Revival

Then along came Samih Sawiris, an Egyptian billionaire. He’d amassed his fortune through his family’s investments in OCI N.V., a global producer and distributor of nitrogen and methanol products, as well as from his construction company, Orascom Development, which builds and operates resorts, including luxurious El Gouna on the Red Sea.

In 2005, Sawiris flew over Andermatt in a military helicopter, invited by a friend in the Swiss defense ministry who’d asked his opinion of what might be done following the departure of the army. Sawiris was impressed by the vast, open mountain terrain, the lack of development and the proximity to Geneva, Zurich and Milan. This eventually led to an invitation from the Swiss government to help develop Andermatt.

Sawiris agreed, with the provision that the authorities would permit him to sell real estate to foreigners, a relatively rare occurrence in Switzerland, which allows foreign ownership only in certain parts of the country. Those sales would help fuel the project. Sawiris also asked for 250 acres to create a mountain development, and the decision was put to local residents as a referendum. Ninety-six percent of Andermatt’s citizens agreed, and the regional and Swiss governments also backed the project—remarkable in a country where the bureaucracy can be daunting.

The reaction in the ski world went from eye-rolling to astonishment in the blink of an eye. Andermatt, that half-forgotten mountain town with remnants of an army presence and vintage infrastructure, was suddenly the recipient of development worth approximately $1.4 billion. The changes started with a bang, thanks to the construction of the Chedi, an opulent five-star hotel (and sister property of the Chedi Muscat in Oman) that was built where the Grand Hotel Bellevue had once stood. Winter rates start at around $1,000 a night; if you want to own, prices at the hotel’s residences begin at $1.8 million.

Then came three Michelin-starred restaurants and the brand-new, 650-seat Andermatt Concert Hall in 2019, with an opening performance by the Berlin Philharmonic. The 18-hole Andermatt Swiss Alps Golf Course was opened, and serious upgrades to the lift system have commenced. There will be 42 multi-million-dollar chalets, and an astonishing 42 luxury apartment buildings are under construction or planned. Prices at a complex like House Steinadler begin at $1.3 million for a one-bedroom unit, with the right to a parking space included (which the developers say is worth about $43,000). Some 30 more apartment buildings are scheduled to roll out in the coming decades, and there will be more four and five-star hotel properties. It is the biggest ski project the Alps (and perhaps the world) has ever seen, and Phase One was completed in 2019.

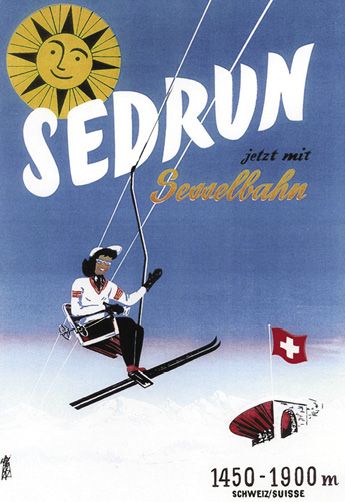

In terms of skiing, the resort stretches beyond Andermatt and its valley to the neighboring resorts of Sedrun and Disentis. The latter lies several valleys away and is famed for its astonishingly beautiful 8th-century Benedictine monastery and for being the heart of Romansch-speaking Switzerland. (The nation’s fourth language is Latin-based and the daily tongue of some 60,000 people.) It’s like traveling to a foreign country within the boundaries of a ski resort, albeit one with about 75 miles of varied terrain, 110 miles of trails and 33 lifts. Ski to Sedrun and take a ski safari to Disentis via the Oberalp Pass, and at day’s end you can board a train to return to Andermatt on the same tracks that the Glacier Express plies every day.

Vail Resorts Steps In

As if this weren’t enough, enter Vail Resorts. The company wanted to expand into Europe, and Andermatt needed a seasoned partner to shoulder some of the workload and financial responsibility for Phase Two of the development. It seemed a perfect fit.

The news became official on March 27, 2022, when Vail Resorts announced that it had made its first European acquisition as the new majority stakeholder of Switzerland’s Andermatt-Sedrun Sport AG—Andermatt for short. The company controls and operates all of Andermatt-Sedrun’s ski-related assets. That includes lifts, most on-mountain restaurants and the ski school operation.

Vail Resorts acquired a 55 percent ownership stake, while the former majority owners retain 40 percent. A smaller group of existing shareholders owns the remaining 5 percent. Vail’s investment is about $160 million, and the company has taken on the operating and marketing responsibility. Some $118 million will be used for improvements at Andermatt.

Vail also immediately included unlimited and unrestricted access to the resort on the 2022–23 Epic Pass. While this is Vail’s first ownership stake in a European resort, Andermatt joins 30 other Alpine resorts already part of the Epic Pass, including five in Austria’s Arlberg and three in France’s Trois Vallées. (Disentis is independently owned and is not part of the Epic Pass.)

Vail plans to replace lifts, upgrade snowmaking and improve and expand on-mountain dining. One senses that this is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s clear that the quiet days of Andermatt are history and that expansion is the route forward, especially with government involvement, private equity and now partial ownership by a publicly traded company. Yet to these eyes, Andermatt still looks relatively tranquil, with plenty of room for more skiers. In a year or two or three, things could be quite different.

Regular contributor Everett Potter wrote about the annual Swann Galleries ski-poster sale in the May-June 2023 issue.