Five locals tell the story of five decades of progress at Whistler Mountain in British Columbia.

By Michel Beaudry

It wasn’t supposed to happen this way. All the ski experts agreed: The place was too stormy, too big and too isolated to succeed. The proposed resort was on the edge of the world, way out on the western coast of Canada, and there wasn’t even a direct road. It was inconceivable that something so different could work.

And they were right...sort of. This was an era when skis were long and boots were low, when being able to “carve a turn” was reserved for elite practitioners. Skiing in the early 1960s was an adventure. Who needed steep slopes and big vertical? Just getting down a mountain was accomplishment enough. To even conceive of such a wild place was a departure from convention. But to actually build it?

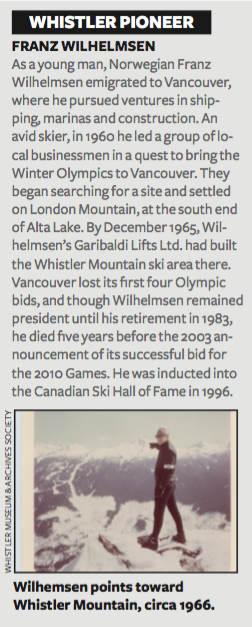

Fortunately, Franz Wilhelmsen didn’t listen to his detractors. Based in Vancouver and well known as an entrepreneur with a air for the dramatic, Franz had seen firsthand what Squaw Valley and Walt Disney had done for the 1960 Winter Olympics. He’d also travelled extensively in the Alps and skied its most famous slopes. He was convinced that British Columbia’s biggest city deserved nothing less than a worldclass, Olympic caliber ski hill. And he knew exactly where to build it.

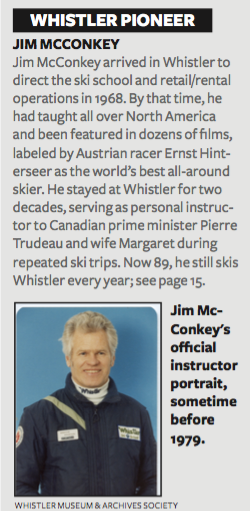

The saga of Whistler Mountain’s construction could fill a book (and it has; for a review of Whistler Blackcomb: 50 Years of Going Beyond, see page 36). Nobody in the North American ski world had built on this scale before. Nobody knew if it was possible. Still, it’s worth noting how much past and future combined in the mountain’s construction: The first ski area to use helicopters to carry the massive load of concrete needed to pour footings for its lift towers, Whistler was also one of the last to use mules and horses to carry supplies to timberline to feed the construction crews living up there.

When the new ski hill offcially opened for business on January 15, 1966, the brash young newcomer didn’t make much of a bang on the international ski front. But for those adventurous enough to make the long trek out to Vancouver and then suffer the white-knuckled four hour drive to Whistler, the ensuing ski experience was something to rave about. What follows is a brief trip through Whistler’s first five decades, seen through the eyes of ve longtime locals.

It’s fair to say that the first ten years of Whistler’s existence were somewhat chaotic. The sheer size of the place—the monster snowfalls, the vicious shifts of weather, the huge vertical—dictated a new form of mountain management.

The mountain had no grooming machines. As for snowmaking, forget it. You skied what was there. Bumps the size of Volkswagens, open creek beds, uncovered stumps, blowdowns, wind crust, sun crust, frozen crud. And to ski from top to bottom, nearly a vertical mile, you had to prepare yourself for screaming thighs and pounding heart.

But the young people kept coming. They came to ski, to party, to explore, to re-invent themselves. Some even settled down. After all, it’s not every day that you stumble onto a magical mountain valley where building lots can be had for under $5,000. By 1971, Whistler’s ski bum reputation was made.

“Whistler was an amazing place to be a local back then,” says Terry (Toulouse) Spence. “There were probably 500 people living here, and we all knew each other.”

Toulouse is one of Whistler’s most revered elders, and something of a trickster figure too. Ever heard of the notorious Toad Hall nude poster? That was the work of Toulouse with photographer friend Chris Speedie (to learn more—and check it out—go to http://blog.whistlermuseum. org/2013/07/10/the-story-of-the-toad-hallposter/). Remember the hard-charging Crazy Canucks? Toulouse was their masseur and start coach for over a decade. Recall the time Prince Charles visited Whistler with his two sons?

It was senior ski-instructor Toulouse who guided them on the mountain.

The one-time Xerox salesman is full of tales. But it’s his stories of early Whistler that are the most fun. “It was Speedie who first invited me to Soo Valley,” he begins. An abandoned lumber camp at the north end of Whistler’s Green Lake, the complex had become the communal home for a group of longhaired skiers who’d solved Whistler’s notorious housing shortage by squatting in the derelict buildings.

“Living conditions were primitive,” he says. “It was very rustic, especially in winter. I would sleep inside three sleeping bags, and still wake up freezing!”

But they had fun. Take the notorious 1973 St Patrick’s Day affair. “Well,” he begins, “nudity wasn’t that big a deal in the old days and...” Again, it was a Speedie and Toulouse caper. This time the two comedians doffed their clothes at the summit’s Roundhouse Lodge, and fortied by a few hits of Irish whiskey, streaked the popular Green Chair zone wearing nothing but skis and boots.

“We skied right under the chairlift,” says Toulouse, who now helps his wife, Anne, run one of Whistler’s most popular bed-and-breakfasts. “We had a pretty good laugh at the shocked faces staring down at us.

“You know, I moved to this place for the skiing,” adds the 73-year-old. “But I stayed for the people.”

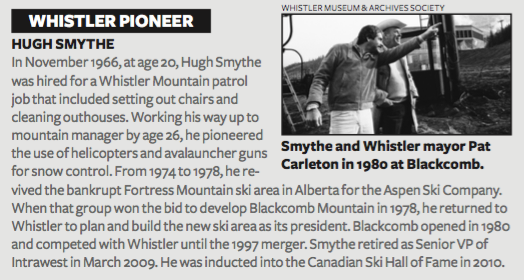

The next ten years ushered in some of the biggest changes in the young resort’s history. In 1980, Blackcomb opened with 24 runs and 350 acres on the next peak north, facing Whistler’s new northside lifts. Between them, in the new pedestrianonly village—planned and built from scratch—guests could access two separate ski areas by taking a few steps in either direction. It was bold. It was creative. And it was all due to visionaries like Al Raine and new Blackcomb president Hugh Smythe (remember that name!).

The next ten years ushered in some of the biggest changes in the young resort’s history. In 1980, Blackcomb opened with 24 runs and 350 acres on the next peak north, facing Whistler’s new northside lifts. Between them, in the new pedestrianonly village—planned and built from scratch—guests could access two separate ski areas by taking a few steps in either direction. It was bold. It was creative. And it was all due to visionaries like Al Raine and new Blackcomb president Hugh Smythe (remember that name!).

In the meantime, Whistler’s staff was engrossed in the technical challenges of operating such a vast and dangerous physical plant. The ski game had also changed. Supported by highbacked boots and stronger and more flexible skis, the skiers of the mid-1970s were venturing far beyond their elders’ tracks.

This totally changed the game for the Whistler Mountain ski patrol. Led by Smythe—who would soon leave Whistler’s employ to launch Blackcomb next door—the team devised an innovative avalanche control plan whose modus was to control the danger points within the ski area by bombing the critical start zones.

It may sound like old hat today, but back then it was leading-edge stuff that sparked the imaginations of young skiers like Cathy Jewett. Originally from southern Ontario, the outgoing teenager had moved west to live the Whistler dream. She was hired in 1976 as a lift attendant, only to be greeted by one of the worst ski seasons in history. “My first work memory is getting sent to the Green Chair area to shovel snow onto the runs,” she says. “I was skiing through snow with grass sticking out.”

Cathy can recall the exact date she decided to become a patroller. “It was March 10, 1977. A big storm cycle had just come through, and Shale Slope, a classic north-facing pitch, looked particularly inviting.” She sighs. “They didn’t bomb it, so I knew how good the skiing would be. Faceshots at every turn.” She grins. “It was at that point that I found my life’s work: Throw bombs. Ski powder. Cheat death. And save lives.”

Her dream wouldn’t come true until 1980, when Whistler Mountain was forced by the sheer size of the new expansion to hire more women. Thirty five years later, she’s still “Joe patroller,” she says. “I don’t have any special skills. I’m not the weather forecaster or the avi expert. I just pick up injured skiers. Still, I’m proud of what I do. Proud of what I’ve accomplished.”

When real estate developer Joe Houssian met Blackcomb Mountain boss Hugh Smythe in the mid-1980s, few observers realized that ski culture in the Whistler Valley would never be the same. The Vancouver-based Houssian quickly understood that British Columbia’s ski area development policy favored the bold.

When real estate developer Joe Houssian met Blackcomb Mountain boss Hugh Smythe in the mid-1980s, few observers realized that ski culture in the Whistler Valley would never be the same. The Vancouver-based Houssian quickly understood that British Columbia’s ski area development policy favored the bold.

The essence of the policy was straightforward: The more lifts a ski area built on the mountain, the more valley land the provincial government would provide for real estate sales. But no one had ever pushed the model to its logical conclusion.

That is, until Smythe and Houssian teamed up. Millions were invested in new mountain infrastructure. More millions were spent on ashy advertising and sophisticated sales campaigns. Flush with cash and armed with a newly revised master plan, Smythe spent money on high-speed detachable quads like a kid in a candy shop. By 1986, Blackcomb was transformed and Houssian’s real-estate investments started to pay dividends.

Meanwhile, Whistler’s reputation was also on the rise. Local hero Rob Boyd triumphed on its vaunted World Cup downhill course in 1989 and the victory cemented the valley’s reputation as a “go for it” kind of place. Whistler was cool; it had mystique.

Mike Varrin arrived in the early 1990s. “Those were the days when there were still fierce mountain loyalties,” he says. “Back then you were either a Whistler skier or a Blackcomb skier. And the twain never met.”

Varrin had been recruited to take over Merlin’s, Blackcomb’s lucrative après ski bar. He had only one mission: “My new boss told me: ‘I want you to break some rules!’ And that was it. I just had to make sure my bar was more popular than any of their bars.”

Varrin had been recruited to take over Merlin’s, Blackcomb’s lucrative après ski bar. He had only one mission: “My new boss told me: ‘I want you to break some rules!’ And that was it. I just had to make sure my bar was more popular than any of their bars.”

Varrin wasn’t going to let that opportunity slip through his fingers. Every local remembers the afternoon when über entertainer Guitar Doug came ying down onto Blackcomb Square on a tandem paraglider, singing and playing his guitar. “The whole patio at Merlin’s is looking up and screaming,” he says. “Doug has this shtick, where at the beginning of his show he calls out: ‘Who’s thirsty?’ Well, as he’s floating down to earth, he calls it out and everyone on the patio responds. Meanwhile I have 75 jugs of margaritas ready to go, one for each table. And while we’re serving them, the bylaw of cer is right at my elbow saying, ‘You can’t do this...’.”

The Reverend Mike (yes, he’s a legitimate preacher) says his hijinks are now mostly behind him. Since the turn of the century, Mike has worked as Manager of Bars for Whistler Blackcomb, overseeing some of the most popular drinking establishments in the valley. “These days, I’d rather be home playing with my two kids,” he says. “That’s why I have young staff. They can represent while I go home to bed.”

The Reverend Mike (yes, he’s a legitimate preacher) says his hijinks are now mostly behind him. Since the turn of the century, Mike has worked as Manager of Bars for Whistler Blackcomb, overseeing some of the most popular drinking establishments in the valley. “These days, I’d rather be home playing with my two kids,” he says. “That’s why I have young staff. They can represent while I go home to bed.”

Nobody predicted how fast Whistler would grow in the 1980s and 1990s. But as the turn-of-the-century approached, the big little ski hill that could became a leading destination resort. The turning point had come with the 1997 merger of the two mountains under Intrawest, anchored by a village that featured more drinking establishments per block than just about any other town in North America.

Nobody predicted how fast Whistler would grow in the 1980s and 1990s. But as the turn-of-the-century approached, the big little ski hill that could became a leading destination resort. The turning point had come with the 1997 merger of the two mountains under Intrawest, anchored by a village that featured more drinking establishments per block than just about any other town in North America.

For locals, it was a mixed blessing. The economy was booming and Whistler was getting lots of attention from the global media. But with more than two million skier visits a year, the skibum lifestyle was slowly disappearing. Many of the old guard cashed out and left for Rossland, Fernie, Invermere or Nelson.

But for valley newcomers, Whistler was everything they had dreamed about. And when Vancouver beat the odds in 2003 and won the 2010 Winter Games, after a string of failed Olympic bids, the community’s stock soared.

Like many others, Anik Champoux came for the skiing, landing a job with the Whistler Blackcomb ski school in January 2001. “My friend and I were on Eastern carving skis,” she says, “and our supervisor took us up Blackcomb to Spanky’s. It was so steep and wild...we were terrified! But there’s no way we were gonna give up.” The next day the two women bought fat skis, and she passed her Level 4 certication—the Holy Grail for many Canadian ski instructors—in 2005.

“Three women from Whistler Blackcomb passed their Level 4 that year,” she says. “It turned into a big deal: It was the first time something like this had happened, and it sparked big changes in ski school culture. We’d shown there was no difference in technical skiing between male and female skiers!”

But teaching was only a parttime job, and Champoux wanted more. In 2007 she joined the Whistler Blackcomb marketing department and by the fall of 2013, she was named Brand and Content Marketing Manager. “It’s my dream job,” she says. “It’s all about driving the mountain’s narrative. Making this place come alive for people.”

Today, Whistler is far more than a ski town. It’s a year-round resort with a booming summer season fueled by mountain biking and hardcore sports. The calendar includes the Ironman, Crankworx Festival, Tough Mudder and a host of Red Bull sponsored bike contests.

Today, Whistler is far more than a ski town. It’s a year-round resort with a booming summer season fueled by mountain biking and hardcore sports. The calendar includes the Ironman, Crankworx Festival, Tough Mudder and a host of Red Bull sponsored bike contests.

Claire Daniels was born and raised in Whistler. Her mom Kashi started skiing here in the 1960s as a pony-tailed teenager, her dad Bob not much later. They met on the mountain in the early 1970s, fell in love and set down roots. Both belong to that little group of iconoclasts who chose to settle here before there was a village, before Whistler went global.

Maybe that’s why their oldest daughter Claire exemplifies so much of what is good about this community. A veteran traveller, elite trail runner and cyclist, top-ranked triathlete, and skier and snowboarder sans-pareil, Claire also has a master’s degree in planning and works for the Squamish Lillooet Regional District.

Growing up in the valley, she says, was a wonderful experience... particularly if you like being outside. “There’s always somebody up for an adventure,” she says. “As a kid, the sports performance bar is so high, you don’t realize how tough an athlete you are until you leave.”

But Whistler’s still not an easy place to live, particularly if you’re young. “Whistler is an intentional community,” she says. “Choosing to live here is not a casual decision.”

She knows this firsthand. Many of her peers have left, and most will never be able to afford a home here. “It wasn’t always easy to grow up in this place,” she says. “We were—and are—privileged. But Whistler kept changing so fast, sometimes the local kids didn’t know where they fit in. Our ‘sense of place’ was really tested.”

Articulate, thoughtful, intelligent—the 29-year old seems to have it all. But Claire is far from unique. Whistler’s children are scholars and Olympic medalists and award winning artists; they’re scientists, activists and lmmakers. Some are in nearby Squamish, others live in Pemberton, many are dispersed around the world. Still, they’re a fitting tribute to the community that conspired to bring them up. It’s the stuff great ski towns are made of.

A Whistler skier since the 1970s, Michel Beaudry is an award winning mountain storyteller and poet. "Whistler Pioneers" text adapted from Whistler-Blackcomb: 50 Years of Going Beyond by Leslie Anthony and Penelope Buswell. This article was funded by the Canadian Ski Hall of Fame and Museum through a grant from the Chawkers Foundation.