Short Turns: Why Garibaldi at Squamish Failed

The planned glamour resort in British Columbia appeared to have everything it needed to succeed—until it didn’t.

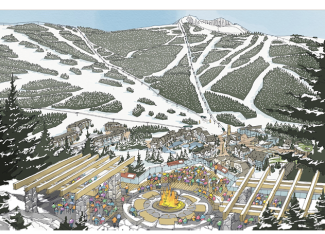

Starting in the late 1950s, development of a new resort in British Columbia gained speed—and lots of media coverage, including (above, courtesy PWL Landscape Architecture) a rendering of its luxury layout. An $80 million bankruptcy followed in December 2023, closing the door on the project—for now.

The six-decade drama surrounding a proposed massive resort development on Brohm Ridge, near Squamish, British Columbia, is seemingly in limbo, despite a new owner emerging from bankruptcy in 2023. The Aquilini Investment Group, one-time partners in the project, gained solitary control after a stalking horse bid was accepted by the receiver to settle an $80 million bankruptcy on the property.

Since then, the Aquilini group has made little progress in meeting the environmental or site requirements set out in the Environmental Assessment Certificate awarded to the development in 2016. The British Columbia Environmental Assessment Office (EAO) overseeing the Garibaldi at Squamish venture has not yet granted an extension to the new owners and there's little evidence of any current on-site activity. If completed, the new complex would be the first true purpose-built destination resort developed in Canada since Blackcomb Mountain opened in December 1980. The hype started on December 27, 1958, with a front-page banner headline in the Vancouver Sun enthusiastically declaring, “Huge New Resort for Garibaldi, Plan Will Cost $5.5 Million.”

Just months after the paving of Highway 99 from Vancouver to Squamish, Adi F. Bauer, an Austrian mechanical engineer, proclaimed that European financing had been procured to build a sprawling ski resort, event center and luxury hotel on the flanks of Mount Garibaldi that would “host everything from major business conventions to the Winter Olympics.” Bauer anticipated that construction could “start in less than six weeks.”

Given such optimism, it’s hard to believe that another headline—dated May 8, 2024, on Vancouver’s Daily Hive website—would echo the same message: “New Garibaldi at Squamish Owners Have a Tight Deadline to Start Construction.”

Indeed, nothing, and everything, has happened in the ensuing 66 years since that first headline. In 1966, after numerous financing delays, Bauer finally completed the Royal Alpine Hotel, though it was never opened to the public. A few lift towers were encased in concrete, but the project stalled by 1969.

Eight years later, a B.C. government initiative investigated the economic viability not only of Brohm Ridge but of other regions in the province that could attract international investment and help diversify local economies away from logging, mining and ranching.

The 19 pages devoted to Brohm Ridge were a withering assessment of the resort’s potential; categorized as an “unacceptable site” due to “excessively steep grades and rocky faces and inadequate snowfall at the Village site.” Oddly, only four years later, the B.C. government would invite an LA–based, but Victoria, B.C.–born, entrepreneur to evaluate the site. Wolfgang Richter came to a very different conclusion, believing that Garibaldi Alpen (as the project was called) would be a splendid day-use area, one that would, instead of competing with the likes of Whistler-Blackcomb, draw skiers away from Cypress, Grouse and Seymour.

That first effort to build a day-use area was rejected, but Richter was encouraged to try again in 1996, when his new company, Garibaldi at Squamish (GAS), beat out two other candidates. Richter was charismatic and engaging, and apparently a damned good telemark skier. He wanted Canadian ownership and to work with local outdoors enthusiasts to increase access to the area.

In 2007, he got his wish when two of Vancouver’s most prominent developers got involved—the Aquilini family, owners of a portfolio of office buildings as well as the NHL’s Vancouver Canucks, and the Gaglardi family, owners of Grouse Mountain and Revelstoke Mountain Resort. The two families put aside previous business rivalries and agreed to work together to develop a four-season resort known as Garibaldi at Squamish, with Richter the vice chairman of the effort.

From 2001 to 2016, the Gaglardi/Aquilini team, working with several overlapping government agencies, the Squamish First Nation and the Squamish city council, set in motion an 8,000-acre plan that would be developed in three stages. In 2016, the province's EAO bestowed its first certificate for a four-season resort.

What the GAS proponents eventually received approval for was breathtaking. At build-out in 2040, Garibaldi at Squamish would have 1,635 acres of skiable terrain on 131 trails, 21 lifts, a 17,538 visitor capacity, 3,045 employees and close to 22,000 beds and 1,184 single-family dwellings.

The devil seemed to be in the details. Far from being a rubber stamp, more than 33 conditions were appended to the certificate that the developers had to meet before officially opening the resort. That’s when relations between the Aquilinis and the Gaglardis started to fray. Now that they had won the coveted certificate, they could not agree upon how to proceed, nor where the money might come from to even start the project.

The complexities of untangling what is happening at a proposed resort, where bank vaults of dollars have been spent on geotechnical planning, lawyers’ and consultants’ fees, bank loans and debt financing—with nary a lift built, a trail cut or a road improved—are challenging.

In December 2023, Garibaldi at Squamish declared bankruptcy and three weeks later, court documents show that a stalking horse bid by the Aquilini group priced the resort’s assets at approximately $80 million. GAS’s ownership structure involved numbered companies loaning funds for the project in a rather unseemly manner; the provincial government initiated an investigation into whether there was a conflict of interest between the company’s directors and how its debt was being managed.

Acting on behalf of the government, Ernst & Young managed the bankruptcy process. The $80 million price tag seemed to be a valuation based on the successful completion of the estimated $3.5 billion project. With a build-out timeline of more than 30 years, substantial investment would be required to recoup the costs. Eventually, years of shaky financing compounded by concerns over environmental impacts derailed the project—for now.

As of summer 2025, no crews are engaged in typical pre-construction tasks. It’s widely speculated that the Aquilinis, for whom $80 million is nearly a rounding error after two decades of investment, might leverage the debt to avoid paying taxes on other parts of their extensive real estate portfolio.

Boasting a major destination mountain resort or not, the Crown land is buzzing. Sea to Sky Highway locals with a sturdy truck, dirt bikes, an ATV or snowmobile enjoy a massive motorized-approved recreation zone. You’ll see Toyota Tacomas dragging trailers into the backcountry bearing out-of-province plates at all times of the year.

Snapshots in Time

1936 Beginner Tips

Skis must be continually waxed with one of some 50 brands of wax. Experts make their own waxes by secret formulas. Far more important to the beginner than all this expertism is getting the rigid connection between shoe and ski. Bindings lash the toe to the ski, but the bindings must also be secure enough to keep the heel from sliding off the side of the ski. Otherwise, the skier, trying to turn his ski, only turns his foot, and falls down. — “Skiing Can Be Risky and Lonely” (Life, December 1936)

1969 New Hampshire Milestone

The Cranmore Mountain ski center is observing the 30th anniversary of the founding of its Hannes Schneider Ski School. It was in 1938 that the late Harvey Gibson spirited the renowned skimeister, Hannes Schneider, out of Austria, despite Hitler’s tight security measures, so that he could bring the Arlberg (old Austrian) technique of skiing to the United States. Mr. Schneider’s welcome here was impressive. As he left the train at the picturesque North Conway station of the Boston & Maine Railroad, local schoolchildren made an arch of ski poles through which he and his family walked. — “A Skiing Milestone in New Hampshire” (New York Times, January 19, 1969, )

1971 The Last Craftsman?

When I was young, If you were a racer, you had to have a pair of Moli’s to be tough: three years to break in, etc. Karl Molitor also handmade a climbing boot called the EIS boot. It was a technical ice-and rock-climbing boot. This boot, like his ski boots, was highly regarded around the world. The two shops in the country that carried the boot for a time (Yvon Chouinard being one of these) described the boot as “the best in the world.” From what I understand Karl has retired, with no one to continue making his boots, either ski or mountain. Raichle may have some of his patents, but Karl’s hands no longer make the boots (a significant difference). — Ken Gallard, Taos Ski Valley, New Mexico, “The Last Craftsman?” (Letters, Powder, December 1977)

1989 Garden State Skiing

The New Jersey ski industry is struggling for recognition, say the operators of the state’s six ski areas. “We have been too long in the shadow of the Catskills and Poconos,’” said Vernon Merritt, president of the New Jersey Ski Area Association. “We offer superior skiing here but have to work toward establishing a stronger identity in people’s minds between skiing and the Garden State.” Although a campaign to promote skiing in New Jersey, begun three years ago by the State Division of Travel and Tourism, increased skier traffic by 20 percent, the industry suffered a setback this season, after most of these funds were reallocated to Shore resorts. — Lyn Mautner, “Ski Resorts Seeking New Image” (New York Times, February 5, 1989, )

1998 Does Size Matter?

Fortunately, skiing goes beyond numbers to the realms of adrenaline, freedom and soul. The reason people continue to ski long boards, despite the current market trend to go shorter, is the simple fact that it feels damn good. Long skis are fleet and stable, and they glide through crud and powder like grandpa’s Caddy—and they impart a feeling of reward and transcendence to the skier capable of piloting them. Training wheels eased our entry into safe biking. But once we ride without teetering, we discarded this training aid. — David Peck, “Does Size Matter?” (Powder, Spring 1998)

2025 My Battle with PTSD

My therapist is the one who first brought up the idea of looking at things from the lens of PTSD. With me, I also think it’s possible that the crash I had at the beginning of 2024, and then Killington happening … that those two crashes maybe built on one another. My therapist let me know that past trauma can sometimes affect your reaction to new traumatic events. Maybe when I crashed and got that puncture wound, maybe that was kind of a perfect-storm situation for PTSD to take hold. — MIKAELA SHIFFRIN, “MY BATTLE WITH PTSD” (THE PLAYERS' TRIBUNE, May 30, 2025)