NASTAR, the world’s largest recreational racing program, began 50 years ago when this editor wanted to introduce the equivalent of golf’s par to the sport of skiing.

By John Fry

The environment for people learning to ski has varied little over the years. Ungainly tip-crossing neophytes are herded into classes of eight to a dozen students. After a day, or perhaps five days, they emerge skilled enough to achieve what they want: to descend the mountain on pleasant trails, while enjoying the scenery and the company of friends.

Most recreational skiers are like golfers who play a round without keeping score, or tennis players happily lobbing the ball back and forth across the net.

Beginning as editor-in-chief of SKI Magazine in the spring of 1964, I worked across the hall from the editorial office of GOLF Magazine, whose editorial director I would become five years later. GOLF’s editors relied heavily on supplying readers with tips to lower their handicaps. Golfers could relate their scores to a PGA player’s sub-par round, or their own putting to Arnold Palmer’s challenge of sinking a 10-footer. How great it would be, I thought, if I could ratchet up SKI’s newsstand sales using the same appeal! How great it would be if it were to become a goal of ski instruction!

At the time, however, it wasn’t an idea especially appealing to the Professional Ski Instructors of America. PSIA’s Official American Ski Technique (later renamed American Teaching Method or ATM) didn’t much resemble what good skiers were doing. They were making stepped turns, using split rotation, and carving on fiberglass skis. Many beginners were learning on short skis with the new Graduated Length Method (GLM). Progressive instructors were looking ahead, but the American Ski Technique was still living in its Austrian past.

Even the name “American” looked outdated. Nationalistic differences in technique were rapidly dying. I set up a cover photo, in which three skiers—Austrian gold medalist Pepi Stiegler, French pro champion Adrien Duvillard, and Canada’s Ernie McCulloch—were seen together in a slalom flush. All three made roughly the same turn. It didn’t look much like the final form of PSIA’s American Ski Technique.

My thinking was heavily influenced too when in 1967 I arranged for Georges Joubert’s and Jean Vuarnet’s bestselling Comment Se Perfectionner à Ski to be published in English as How to Ski the New French Way. The principal way for skiers to advance their technique, the authors believed, was to mimic the actions of champion racers.

SKI’s racing editor Tom Corcoran wrote a column condemning the gulf between racing and what recreational skiers were being taught. He lauded an innovation at Sun Valley. The resort had cordoned off a special slope, not too steep, dedicated to timing recreational skiers as they made runs through easy open gates. It was the equivalent in golf of a Par-3 course. Mont Tremblant Ski School director Ernie McCulloch also made pupils learn how to turn through gates.

Resorts like Sun Valley and Tremblant staged standard races for guests. Entrants who ran the course within a set time limit received a shoulder patch, and possibly a gold, silver or a bronze pin. The prestigious standard races were not necessarily easy—they could be long and challenging. You could compare yourself to others who’d been in the race, but not directly to someone who wasn’t in it. Your rating was only good for the day of the competition. By contrast, a consistent 10-handicap golfer knows that on any day, on any course, he’s likely to play 10 strokes better than a 20-handicapper.

THE SCORELESS SPORT

In October of 1967 I wrote to complain that skiing was virtually a Scoreless Sport, the title I used for my editor’s column in SKI Magazine. I spent much of the subsequent winter asking race officials and instructors how the equivalent of golf’s handicap could be created for skiers.

One weekend at Mt. Snow in Vermont the ski school director, a French Canadian, told me about France’s Ecole de Ski Nationale Chamois program. For certification, an instructor had to perform well enough in the Ecole’s annual Challenge, a classic slalom course with hairpins and flushes, to earn a silver medal—that is, be less than 25 percent behind the time recorded by the fastest instructor. Back at his home area, the certified instructor could set the pace for local participants in a Chamois race—a single run slalom. Gold, silver and bronze were awarded according to the percentage the skier’s time lagged behind the pacesetter’s.

It didn’t take long for the dim bulb in my cerebrum to light up: Use time percentages, not raw times, to rate skier performance. And do it, not with a difficult slalom, but rather by offering a simple open-gate setting on intermediate terrain, anticipated by Corcoran. (In 1972, France’s National Ski School—after three or four years of experimentation—introduced the Flèche, a separate, easier test than Chamois—an open-gated giant slalom similar to a NASTAR course.)

It didn’t take long for the dim bulb in my cerebrum to light up: Use time percentages, not raw times, to rate skier performance. And do it, not with a difficult slalom, but rather by offering a simple open-gate setting on intermediate terrain, anticipated by Corcoran. (In 1972, France’s National Ski School—after three or four years of experimentation—introduced the Flèche, a separate, easier test than Chamois—an open-gated giant slalom similar to a NASTAR course.)

Here was an unwitting, unconscious, unintended collaboration between a French program, little known in North America, and an American program that would blossom into something much bigger, imitated in other countries, enabling tens of thousands of recreational skiers to measure their ability, and glimpse into what it might feel like to be racing in the Olympics.

RACE RATINGS VALID ANYWHERE, ANY TIME

In France a skier participating in Chamois was rated against the local pacesetter’s time, which was not corrected to account for the percentage by which the instructor had lagged behind the fastest time when he’d competed against other instructors. Adjusting the local pacesetter’s time so there’d be a national standard was a vision I had for NASTAR. (Twenty years later, in 1987–88, France adopted the NASTAR principle of speeding up the local pacesetter’s time to create a single standard for a Chamois rating.)

In my mind, the fastest time should be that of a top racer on the U.S. Ski Team. It would work as follows, I imagined. If pacesetter Klaus at Mount Snow was originally three percent slower than the nation’s fastest racer, and a Mount Snow guest was 20 percent slower than Klaus, then he or she would be about 23 percent slower than America’s fastest skier would have been if he’d skied the Mt. Snow course that day. Presto! The skier would have a 23 handicap. The sport of skiing could enjoy the equivalent of golf’s par! A skier would know that on any slope anywhere, through a couple of dozen gates, on a surface that could be sticky or icy, it didn’t matter, the rating would be valid. If he or she had a 23 NASTAR handicap, he was seven percentage points better than someone with a 30 rating.

The possibilities seemed limitless. You could make the results of races around the country equivalent to one another. You could take two equally rated skiers and put them in an exciting head-to-head race. Or you could handicap two unequal racers, delay the start of the better skier, and maximize their chances of reaching the finish line at the same time, making it appear to be an exciting race. On a 300-foot-vertical Michigan hill, you could have a competitive experience equivalent to one at a Rocky Mountain resort.

What I had in mind was a national standard race. I gave it the acronym NASTAR.

The NASTAR idea needed an infusion of money to become a reality, and so SKI Magazine flew me to Chicago to meet with a potential sponsor, the now-defunct Schlitz brewery. I explained the concept to them. The Schlitz guys liked it.

“The program’s called NASTAR,” I explained.

“No, no. It’s got to be the Schlitz Open,” the ad agency guy shot back.

Returning home, I told my wife, who is German, that the meeting had gone well, but that we were stuck on the name.

“What is it?” she asked.

“The Schlitz Open,” I replied. She shrieked with laughter.

“What are you laughing about?”

“Schlitz is our word for the fly on a man’s pants!”

The next day, I phoned the advertising agency in Chicago and told them the news. Within hours, I received a return call informing me that Schlitz had agreed to the name NASTAR.

JIMMIE HEUGA

In December 1968, with Tom Corcoran’s indispensable help, the pacesetting trials took place at his new Waterville Valley resort in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. For the first time, an idea that had existed only on paper became a physical reality.

Jimmie Heuga clocked the fastest times, earning the title of national pacesetter. Charlie Gibson, a tall, spare, laconic mathematics whiz from IBM, who would later become president of the U.S. Ski Association, developed statistical tables, by which local ski areas could compute the handicap ratings of recreational skiers. Gloria Chadwick, a perpetually cheerful, obsessively organized New Englander, quit her job running the U.S. Ski Association in order to manage NASTAR.

In the winter months of 1969, NASTAR’s first season, 2,500 recreational skiers competed at eight areas across the country—from Mt. Snow in Vermont to Alpental in Washington, and at Vail, where the charismatic Swiss champion Roger Staub had become ski school director.

The standard for winning gold, silver and bronze pins was different for men and women. Two winters later, the standards for medal winning began to take age into account as well. Response was upbeat. The well-known New York Times ski columnist Mike Strauss said that “NASTAR is the best thing to happen to skiing since the introduction of the rope tow.”

The standard for winning gold, silver and bronze pins was different for men and women. Two winters later, the standards for medal winning began to take age into account as well. Response was upbeat. The well-known New York Times ski columnist Mike Strauss said that “NASTAR is the best thing to happen to skiing since the introduction of the rope tow.”

SANDBAGGING ON SKIS?

At the end of the first season, Schlitz flew 39 successful NASTAR medalists to a final race at Heavenly Valley, California. They raced head-to-head, starting with times adjusted by their handicaps. It didn’t occur to me that competitors might contrive to inflate their handicaps—the practice known as sandbagging in golf. The Minneapolis Star’s ski columnist Ralph Thornton wrote a column suggesting the possibility that some racers had sandbagged, cheating Midwest skiers of victory.

Well, I thought, if the race was worth cheating at, NASTAR is clearly a success.

How to enhance NASTAR’s popularity? One possibility was to incorporate the program into ski schools, as an objective way for instructors to measure the progress of students. I proposed the idea to the Professional Ski Instructors of America.

Many people, I argued, are able to ski proficiently, even elegantly, when they’re able to choose anywhere to make a turn. The instructor observes, applauds the student’s form, and advances him to a higher class. But what about making a must-do turn, at high speed, to avoid a tree? What about being forced to enter a gate at the right point in a race? It’s far more difficult to turn at a given spot. The skier must master skills like gliding, skidding, drifting, pivoting, rebounding, absorption and stepping, as well as carving, in order to get specifically from Point A to Point B. Instructors could use NASTAR to monitor people’s advancing skill. The skier’s handicap would become the measure of his progress in taking lessons.

Deficient in powers of persuasion and lacking in political skill, I failed to convince anyone at PSIA, except notably Willy Schaeffler, that the organization, already famously resistant to innovation, should get behind NASTAR.

My other hope was to interest the U.S. Ski Team. By linking the national handicap to the speed of the country’s fastest skiers, NASTAR could serve as a grassroots system to identify young talent for future national teams.

My other hope was to interest the U.S. Ski Team. By linking the national handicap to the speed of the country’s fastest skiers, NASTAR could serve as a grassroots system to identify young talent for future national teams.

MEETING IN A MANHATTAN STEAM ROOM

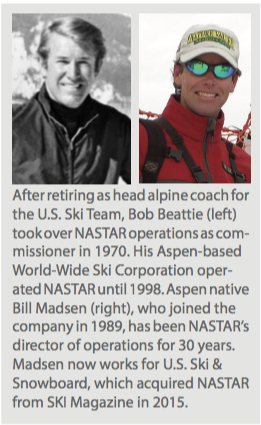

How to persuade the U.S. Ski Team to supply pacesetters? It wouldn’t be easy. Alpine director Bob Beattie preferred to exert control over programs involving the Team. I thought I might have a better chance of gaining Beattie’s support if I could enlist the persuasive Corcoran to talk to him.

One day, when I determined that both Corcoran and the itinerant Beattie would be in New York City, I arranged for us to meet at the New York Athletic Club on Central Park South. When Corcoran and I arrived in the club’s lobby, we learned that Beattie was in the steam room. We were told to meet him there.

Upstairs in the locker room, we stripped. Groping our way into the hot mist of the steam room, we found the perspiring coach. Inside the foggy chamber, Corcoran attempted to convince Beattie of the benefits of a union with NASTAR. It would make the Ski Team visible on the slopes and in the magazine. By tying the times of the best U.S. racers to NASTAR ratings, the Ski Team would enter into the daily awareness of recreational skiers. And a fraction of the recreational skier’s entry fee would be donated to the always sagging Ski Team treasury.

Emerging from the heat of the steam room, his face reddened to the color of a scalded beet’s interior, Beattie appeared to me to be unconvinced. What I didn’t know was that the coach himself was concocting in his mind his own five-year, multi-million-dollar plan. Called the Buddy Werner League, it aimed—like Little League baseball—at tapping into 250,000 young athletes, through a program named after the late U.S. racing star.

BEATTIE REIGNS FOR 30 YEARS

Although the trip to the steam room had been a failure, Beattie’s view of NASTAR changed a year later. Retired from the Ski Team, the former coach was seeking entrepreneurial opportunities. His search coincided with SKI’s search for a way to keep track of thousands of entries at a rapidly rising number of ski areas wanting to join in hosting the popular new races.

Although the trip to the steam room had been a failure, Beattie’s view of NASTAR changed a year later. Retired from the Ski Team, the former coach was seeking entrepreneurial opportunities. His search coincided with SKI’s search for a way to keep track of thousands of entries at a rapidly rising number of ski areas wanting to join in hosting the popular new races.

Off-site computers and software didn’t exist at the time. To pay for the labor-intensive organization, a way had to be found, not only to make ski areas pay, but to extract money from sponsors like Pepsi and Bonne Belle as well as Schlitz.

Under license from SKI, Beattie took over the operation of the program that he had once spurned. He was the ideal guy to run it. In NASTAR’s second season, the number of participating ski areas grew to thirty-nine. Sponsorships proliferated. Resorts took in money from guests willing to pay to race. Offshoot programs were created—like Pepsi Junior NASTAR and Hi-Star for interscholastic competition.

Fifteen winters later, prodded and promoted by the former Ski Team coach, who was now also pro racing impresario and TV commentator, NASTAR grew to 135 areas, attracting a quarter of a million recreational racers each winter. In Canada Molson’s Beer launched a copycat Molstar program. NASTAR clones sprouted in Scandinavia, Switzerland and Australia.

In conversations in lift lines and in base lodges, I heard the thrilled voices of intermediate skiers who’d raced for the first time in their lives. Excitedly they compared their handicap ratings. Friends, who’d never before skied competitively, told me of butterflies in their stomach as they stood in the NASTAR starting gate. Children boasted about winning a bronze pin. At a NASTAR finals, where recreational racers from 5 to 85 years of age competed, I saw a helmeted 10-year-old boy and his grandfather hugging one another as they rejoiced over their results.

NASTAR was conceived in the 1960s—the age of Killy, Kidd, Greene and other alpine racing stars. Putting their faces on SKI Magazine’s covers added tens of thousands to newsstand sales. For me, here was material proof of where the interest of readers belonged. In their desire to learn from racing I was a believer.

John Fry is the author of The Story of Modern Skiing, a history of the revolution in technique, teaching, competition, equipment and resorts that took place after World War II. In 1969 through most of the 1970s, he was editorial director of GOLF Magazine, as well as of SKI. He is indebted to veteran ski moniteurs Gerard Bouvier and J-F Lanvers for obtaining fresh historical information about France’s Chamois and Flèche programs.