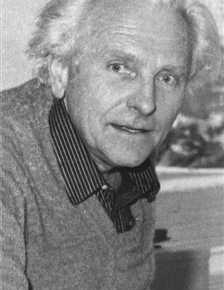

Georges Salomon - Georges Salomon, Legendary equipment manufacturer

Legendary equipment manufacturer

Georges Salomon, arguably the most influential figure in the ski manufacturing world during the second half of the 20th century, passed away October 5, 2010, at his lakeside home in Annecy, France. He was 85.

The company that still bears his family name began in 1947 as a three-person business (Georges, father François and mother Jeanne) in a one-room metalworking shop that François had purchased to make saw blades. Soon after, they adapted their machinery to make metal edges for skis, and a legendary manufacturing and marketing brand was born.

It wasn’t much of a reach for the nascent company to migrate from ski edges to the primitive cable bindings of the era, where the brand made its first big splash with the Skade toe piece in 1955. Bindings remained the company’s principal activity until it launched its first boot, the rear-entry SX90, in 1979. In the decade that followed Salomon dominated headlines with the introduction of the SX90’s successor, the hugely successful SX91, followed by an integrated cross-country boot-binding system, SNS, which quickly gobbled up an amazing market share, and culminating in 1989 with the arrival of a line of monocoque skis. In 1985 the company acquired the Taylor Made golf brand, which in time would become its most valuable asset.

This suite of successful diversifications established the brand’s reputation as the innovator in the ski domain, but Salomon was rarely the first to market. The releasable toe piece, the ski brake, the step-in heel and the rear-entry boot were not, in fact, invented by Salomon, but it was the genius of the brand that once it entered a field its unique talents for marketing and communication obscured any antecedents. Salomon wrapped its new products in fresh terminology and positioning, essentially changing the dialog with the consumer to the exclusion of other options.

But Salomon’s success had less to do with marketing in the conventional sense than it did with engineering. All of the original brains behind the brand, including Georges, were trained as engineers. It was the bundling of the disciplines of engineering and painstaking market research that created the Salomon magic. Product development often took five years or more, with 80 percent of that time devoted to research and only 20 percent on executing the product and its story. A shrewd and ruthless patent policy – originating in a dispute that the founding family lost back in the saw blade era – contributed greatly to the brand’s dominance.

Georges’ fingerprints were all over every product, as he spent his days wandering through his factory and meeting rooms, often ignoring managers but always with time for the blue-collar workers, whose ideas were often integrated into the production process. When he did interrupt a planning meeting his remarks were terse, on point and sometimes scathing. Once when he shook a binding prototype he heard a rattle; bellowing, “No one is going to put my name on that!” he threw it out the window. This became known to the design team as the dreaded “clickity-clack,” the instant rejection of what may have represented years of work.

When Salomon and Taylor Made were sold to Adidas in 1997 for 9 billion FF (€1.4 billion), Georges’ lifestyle, which had been remarkably modest for most of his career, leapfrogged from merely affluent to posh. Accosted by a colleague shortly after the sale, Salomon was anything but jubilant, lamenting, “Now what am I going to do?” Unharnessed from the daily routine of business, Georges had the contentments of wealth and family but could no longer put his personal imprint on the products that bore his name. He is survived by his wife Perry (née Junod), sons Bernard, Jean-Marc and François and seven grandchildren.