This article and its images are copyrighted extracts from the forthcoming book, Jay Peak, by ISHA member and author Bob Soden. To learn more, go to www.jaypeakhistory.com.

(Above) Photo Courtesy of Jay Peak Resort

How a once-isolated outpost became a busy year-round destination for visitors from the Northeast U.S. and Canada—with investors from around the world. By Bob Soden

Vermont’s Jay Peak is a picturesque 4,000-foot monadnock (a mountain that refuses to be worn down) punctuating the end of the Green Mountains’ 250-mile run up from Massachusetts. To be an isolated sentinel at that lonely post, just five miles from the Canadian border, is both a blessing and a challenge—great snow and 360° views, but the last exit on a skier’s figurative highway.

“How do you get them to go that extra mile?” has been foremost on the minds of Jay’s managers over the years. Jay always has been—and still is—a place for real skiers. The snow and challenging terrain have assured that. But the challenges of its location have required savvy marketing and visionary leaders. Fortunately, Jay has had very good luck in that regard.

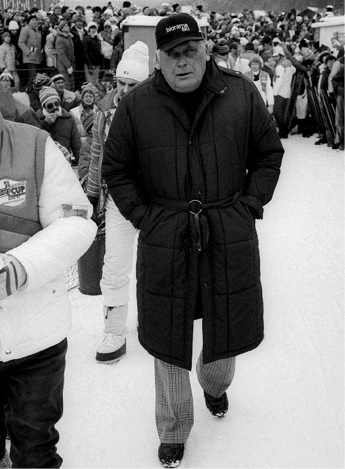

Take Bill Stenger, co-owner and president of today's Jay Peak Resort, who was lured north from Pennsylvania’s Jack Frost ski area during the Mont St. Sauveur International (MSSI) era at Jay. When he arrived in 1985, seven years after the Canadian company had purchased the mountain from the Weyerhaeuser Company (WeyCo) of Seattle, skier traffic had stalled at 78,000 visits annually. The infatuation of Montreal skiers with the south-of-the-border mountain was starting to wear off. Today, Canada accounts for 55 percent of Jay’s 400,000 skier-days a year. How did Stenger turn it around?

First, he upgraded the mountain’s tired uphill facilities. Then he did what all Jay Peak managers have done if they wanted Jay to succeed—he offered skiers something they couldn’t find elsewhere.

He found it in a lift line. Or more specifically, covering a pod of young skiers in the line in front of him. The kids were dusted with powder, which was odd, because the sky was decidedly blue. It turned out, as the miscreants mumbled, the powder came from their off-piste antics.

A quick study, Stenger realized that here was something different. Jay Peak, overlooking the flat Quebec plain, stretching 70 miles west-northwest to the Canadian metropolis, works as a foil on westerly storms, precipitating huge powder dumps on the mountain’s flanks. With proper marketing and judicious culling, Jay’s wild glades could be domesticated and enlarged. That would be the calling card that would bring skiers and snowboarders from all over the Northeast and even Europe.

Early Days at Jay

(Right) Photo Courtesy of Jay Peak Resort. Bill Stenger, president and co-owner, has turned the mountain around--and weathered a few storms--since arriving in 1985.

Back in 1940, some skiers from the nearby town of Newport founded the Jay Peak Outing Club (emulating the Mount Mansfield Outing Club) and, in a leap of faith, built a ski jump in the foothills of Jay Peak. Two journalists, brothers Wallace and Earnest Gilpin, who worked at newspapers on opposite sides of the mountain, had been editorializing for years on how the region needed to be developed as a year-round recreation destination. But a problem remained—you couldn’t get there from here. So a road was built: Route 105A.

The challenge was the same in 1953 when a young North Troy high school teacher, Harold Haynes, had 4,000-foot dreams. Stowe had succeeded and now Sterling Mountain in Jeffersonville was in the running. How could he divert the economic snow train to his neck of the woods—the Northeast Kingdom?

So Haynes and the local Kiwanis Club boosted the idea in town halls and state legislature lobbies. Guided by the wise counsel of “The Father of Vermont Skiing,” state forester Perry Merrill, the state acquired 1,400 acres of what would become the Jay State Forest. By 1955 Jay Peak was incorporated. The advice of Charlie Lord of Stowe—a highway engineer who had worked with Merrill to cut the first trail on Mount Mansfield—was sought. He generously produced a trail and lift sketch, but money was needed to buy a lift.

This was primarily a bootstrap operation. Full-page local newspaper ads touted the economic benefits. Future Jay Peak manager Jim (Porter) Moore went door-to-door and farm-to-farm selling shares at $10 a pop. As he later related, “Folks would sell a cow and buy a share.” With the help of a sports-car-driving, jaunty-cap-wearing Catholic priest from Richford, Fr. George St. Onge (whose nonstop enthusiasms to aid his flock included such projects as a successful hockey stick factory in his home town), the fundraising goals were reached, and a ski lift was ordered from France.

Despite Route 105A, in 1956 Jay remained difficult to reach. Merrill, now the state Commissioner of Forests and Parks, came to the rescue, acquiring a right-of-way over the mountain pass connecting Montgomery Center and North Troy. The Jay State Forest Route, later renamed Route 242, was soon constructed. Later that summer, Merrill and Jay Peak president Haynes would stand at the foot of Jay’s south shoulder and guide the cutting of a lift line and its first trail.

But the new ski area needed more than a lift and a trail. A local vacation homeowner, Rudi Mattessich, just happened to be director of the Austrian Tourist Office in New York City. A few calls overseas and they’d found their man.

When Walter Foeger arrived in December 1956, hired as the area’s sole ski pro, he found one open slope and an unassembled Poma lift. He dropped his Kneissl skis and picked up a wrench—and the lift was completed by the end of the year. In January 1957, in two feet of new snow, he led a team of local woodsmen with chainsaws to cut the beginner-intermediate Sweetheart Trail. That year, he also sold hot dogs, gave lessons to gargantuan ski classes (and free ones to local kids), coaxed a homicidal wooden roller behind him to smooth the area’s two trails, wrote newspaper articles and repeatedly climbed the mountain to lay out additional trails. A year later, as the new mountain manager (and still the only ski pro), Foeger picked up a brush, and the December 1957 issue of SKI Magazine featured an oil painting of a future Jay Peak. By the time he moved on in 1968, a whirlwind twelve years later, during which he had attained the position of General Manager and Vice President, the ski area could boast 46 trails and 7 lifts.

Foeger was promoter, ski theoretician, writer, ski racer (posting a better time than Emile Allais in the 1936 Hahnenkamm downhill and combined), tennis champion (Vermont Seniors’ Tennis Champion many years running), artist, film maker and manager—all wrapped up in one bow-legged “determinedest man I know,” according to former Vermont Gov. Phil Hoff. He had been born in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1917. Growing up in Kitzbühel, he became ball boy at the local tennis court and rink rat on its ice rink in winter, when he wasn’t schussing the backyard Alp. During World War II, he was drafted from the local militia to train Germany’s ski troops. Wounded in Russia, he was sent to Spain to recover and was eventually named coach of its Olympic ski team, which he led to Oslo in 1952.

But what really helped Jay Peak avoid the unfortunate fate of so many New England ski areas in that period—and brought skiers to Jay from Montreal and Boston and New York—was something they couldn’t find elsewhere. That was Foeger’s maverick ski teaching system, Natur Teknik. The technique, eventually taught at more than a dozen ski areas in the eastern U.S. and at one in Japan, was unconventional. It eschewed the use of snowplow or stem: It was parallel from the start! That did the trick, and skiers schussed in.

Gross receipts for 1957 were $4,400; by 1964 they were $271,000. Haynes would often repeat, “Without Walter Foeger, there’d be no Jay Peak.” But despite the ski school’s success, growth was plateauing. Something new was needed to pull in the crowds at Jay.

Deep Corporate Pockets

In 1964, a forestry giant from the West Coast was looking for a way to re-purpose its logged-out lands. It just so happened that WeyCo owned real estate adjoining the Jay State Forest. Impressed by the showing the self-made ski area had made in a brief seven years, and after internal studies on diversification showing profits could be made in the ski and real estate businesses, WeyCo came courting. The company’s overtures were warmly received by Haynes and Foeger and Fr. St. Onge.

WeyCo purchased Jay Peak, Inc. in 1966, arriving with deep pockets. Foeger described his vision of an expanded Jay Peak, encompassing the west “snow bowl,” complete with an Austrian village anchoring a tramway to the top of “Vermont’s Peakedest Peak” (as an early boosting poster touted). WeyCo listened with rapt attention.

A new tram opened in January 1967, just in time to catch tourists heading north that year to Montreal’s EXPO 67. And the new lift did its duty in bringing in the crowds to ride the East’s fastest and longest tramway (Cannon Mountain’s tramway in New Hampshire was an elder statesman from 1937 but would get an upgrade in 1980). WeyCo and Foeger, differing on what development directions they thought the mountain should take, decided to part ways in 1968.

In the early 1970s, the 48-room Hotel Jay and a couple dozen condos were built. Then some bad snow years followed, coupled with the energy crisis, making the extra mile more costly. A corporate change in philosophy on diversification led WeyCo to sell Jay Peak in 1978.

That year, seven owners from Mont St. Sauveur, 45 minutes north of Montreal, heard of WeyCo’s plan and made an offer. The group felt this would offer MSSI’s legions of loyal skiers a way to triple their skiing vertical with a mere doubling of their travel time.

The first changes were the installation of the Green Mountain Chair on the tram side and improved on-mountain bed numbers. But MSSI realized by 1985 it needed an experienced American professional on the ground. They found Bill Stenger, who’d managed Jack Frost in Pennsylvania and doubled skier visits. Stenger had a condition, though: In addition to being mountain manager, he wanted an ownership position. He got it, and that has made all the difference.

A Rising Tide Floats All Boats

Stenger moved quickly, doubling uphill capacity, upgrading the snowmaking and improving the guest services. Skier visits were 78,000 in 1984. By 1996, they were 200,000. Stenger pushed Jay into the glade business, and by 1997 it was voted No.1 in the East for its powder and tree skiing by Snow Country magazine. The area was now the “Jay Peak Ski & Summer Resort.” A championship 18-hole golf course, designed by Graham Cooke, opened in 2007. By then Jay had 76 trails and 8 lifts.

In 2006, after 30 years of ownership, MSSI decided to sell its stake in Jay Peak. Senior shareholder Jacques Hébert had passed away and the remaining shareholder families wanted to go in new directions.

(Left) Photo Credit: Newport Daily Express / Bob Soden Collection. A 1941 Jay Peak Outing Club jumping competition on Mead Hill in North Troy, in the Jay Peak foothills.

About that time, Stenger and a group of interested investors approached Ariel Quiros, an international entrepreneur and longtime Jay skier and local property owner, with a plan to purchase Jay. The deal was concluded in 2008.

Stenger had investigated the potential of investment funding through the federal government’s EB-5 visa program (see box) back in 1997, but immigration policy at that time interfered. He revisited the idea successfully in 2004 under MSSI to fund the new golf course (which opened in 2007). But the partnership would take the concept to a whole new level.

Through the program, Stenger and Quiros have raised in excess of $500 million, and to date Jay Peak has been the beneficiary of more than $200 million in development. Investment has come from at least 60 countries, including China. This funding has underwritten the construction of three new ski-in, ski-out hotels and 250 new condo townhouse units, in total adding 2,500 on-mountain beds (a key feature for the resort’s success) and nine restaurants.

Jay Peak has been known since its inception as a low key, no-frills, friendly ski area “for skiers.” More recently its reputation has grown due to its extensive glades and out-of-boundary skiing, unmatched in the Northeast, and its transformation into a full-fledged four-season resort featuring a 60,000 square-foot water park and an NHL-sized indoor ice hockey/curling rink, among other amenities.

As well, Stenger and Quiros have launched the Northeast Kingdom Economic Development Initiative to benefit the nearby town of Newport (on Lake Memphremagog) by revitalizing its downtown core and waterfront. In addition, they are enlarging the Newport Airport to make it regional-jet capable, thereby providing direct access for its international customers. EB-5 funding to match that of Jay Peak’s is to be involved there.

Stenger and Quiros are very different men, yet similar in many ways: Both started out in sales (Stenger in insurance in Boston, and Quiros selling jeans as a high-school student at a New York City subway station). But they both love skiing and have a quality all Jay Peak managers had to have to be successful—chutzpah.

Stenger, who was named manager of the Jack Frost ski area in the Poconos in 1974 at age 26, has spent more than forty years in the ski business. In the early 1990s, he chaired a national skiing industry marketing committee of the combined NSAA and SIA to increase the number of new skiers nationwide. He was honored in November 2013 with a BEWI award for his transformation of Jay into a year-round resort and continuing efforts on behalf of the U.S. ski industry. In April 2014, Jay Peak received the Vermont Governor’s SMART Award for Creative Marketing in Tourism.

There has been some grumbling of late from local off-mountain innkeepers, bed-and-breakfast operators and restaurateurs, who worry that Jay will diminish their business. Fair enough. But Jay’s philosophy has long been that a healthy ski resort will assure healthy neighbors. And it’s not just paying lip service to the matter: Witness the Newport renaissance soon to be underway. So let us remember what JFK often quoted: “A rising tide floats all boats.”

Irwin at the top of the Gotschnagrat above Klosters with fashion model Bobby Charmoz.

Irwin at the top of the Gotschnagrat above Klosters with fashion model Bobby Charmoz. Left to right: Actor Noel Howard, an unidentified friend, Marian and Irwin Shaw, Jacques Charmoz and Jacqueline Tesseron on the slopes of Parsenn.

Left to right: Actor Noel Howard, an unidentified friend, Marian and Irwin Shaw, Jacques Charmoz and Jacqueline Tesseron on the slopes of Parsenn. Adam Shaw at the top of the Gotschna above Klosters last winter. He now lives in the French Alps

Adam Shaw at the top of the Gotschna above Klosters last winter. He now lives in the French Alps Irwin (far right) and Marian Shaw (far left) in Klosters in the 1960s with the writer Peter Viertel (black hat) and film director Bob Parrish (red and blue parka). Everyone in the group was on Head skis that day.

Irwin (far right) and Marian Shaw (far left) in Klosters in the 1960s with the writer Peter Viertel (black hat) and film director Bob Parrish (red and blue parka). Everyone in the group was on Head skis that day.