Penguin Power!

One of North America’s first and most successful ski clubs was created in Quebec entirely by, and for, women.

By Cara Armstrong and Lori Knowles

Ski clubs have played an important role in the growth of Quebec’s Laurentians as a major North American ski hub, as well as in the development of world-class Canadian racers. And few clubs have been as successful as the Penguin Ski Club, founded in 1932 by a group of young Montrealers—a group consisting entirely of women. In the decades since then, Penguins have won alpine and nordic medals at the Olympic, World Cup, Master’s and national level; been inducted into national and regional halls of fame; and have been awarded some of Canada’s highest honors.

Ski clubs have played an important role in the growth of Quebec’s Laurentians as a major North American ski hub, as well as in the development of world-class Canadian racers. And few clubs have been as successful as the Penguin Ski Club, founded in 1932 by a group of young Montrealers—a group consisting entirely of women. In the decades since then, Penguins have won alpine and nordic medals at the Olympic, World Cup, Master’s and national level; been inducted into national and regional halls of fame; and have been awarded some of Canada’s highest honors.

In the 1933 edition of the Canadian Ski Club Annual, the Penguin’s founder and first president, Betty Sherrard—born in Mexico City, raised in Montreal and educated in England—said the club’s mission was: “to help its members enjoy skiing to the fullest, and to advance the standard of ski proficiency amongst women.” To begin, she recruited fellow female skiers from the Junior League of Montreal and the Canadian Amateur Ski Association. She also worked closely with the all-male Red Birds Ski Club of McGill University, founded in 1928.

While inspired by the Red Birds, the Penguins opted for broader membership criteria. As noted in the club’s official history, The Penguin Ski Club: 1932–1992, the women elected to found their group outside the university as an “important opportunity for young Montreal women to travel, socialize, and stay together [as well as] offer the first ski instruction and competition specifically for women.” Membership was by invitation, and the first recorded meeting was held on March 29, 1934. Members could make nominations and the executive committee would discuss each one. One “blackball” meant the nomination was referred to the committee, and two meant the nominee was out.

Making Headlines

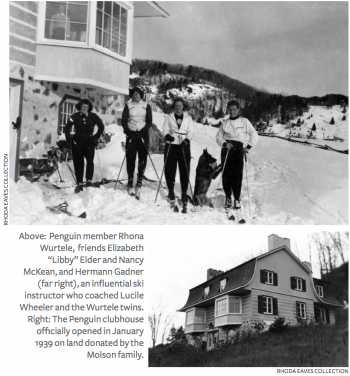

The Penguins began making headlines almost immediately after being formed. Olympic track-and-field gold medalist-turned-journalist, Myrtle Cook, began featuring the club in her sports column, “Women in the Sportlight,” on a regular basis for the Montreal Star. In 1933, the Boston Herald featured a story on this unique all-female group. Both newspapers were fascinated by Duke Dimitri von Leuchtenberg’s work with the club. As a graduate of Hannes Schneider’s Arlberg Ski School and former director of the ski school at Peckett’s-on-Sugar Hill in New Hampshire, von Leuchtenberg had taken on the task of improving the Penguin’s skiing skills and honing their racing technique.

They practiced at Mont Saint-Sauveur, and held their first meet during the winter of 1934. The early competitions included downhill, cross country, jumping, slalom and a bushwhack race. Laurentian ski pioneer Herman “Jackrabbit” Johannsen organized the festivities and set up the bushwhack course down an unmarked slope. From the club history: “‘I remember the bushwhack races,” said Penguin member Percival Ritchie. “They were soon outlawed,” she said. “We would start from the top of a steep, uncleared hill and race straight to the bottom. I ended up in a barbed wire fence, tore my pants and cut my knee. This made me very proud. I still have the scar.’”

In 1935, the Penguins joined the Canadian Amateur Ski Association and began competing in women’s races. In that first year, they participated in eight ski races and won every single one of them. Members of the group continued to either win or place in the top five of the Canadian Championships from 1936 to 1939.

Penguin House: A Home is Built by the Molsons

During their early years, the Penguins led a peripatetic existence. In 1933, club members used two rooms above the Banque National in Saint Sauveur as their base. In 1934, they moved to a house on the “station road” that had three small bedrooms, four cots per room and one bathroom. Members claimed they could “lean out one side of a cot to brush their teeth and out the other side to cook bacon for breakfast!”

Desperate for more space, the club moved the following year to a house in Piedmont, Quebec, but soon determined it was too far away from the ski action. A permanent home was needed. According to the official history, John and Herbert Molson of beer fame stepped in as Penguin patrons in late 1938. The Molsons donated land three-quarters of a mile from Saint Sauveur, as well as the funds for construction of a building for “the fine women who were doing a lot for the Canadian sport (of skiing) and for the enjoyment of the outdoors.” The Penguin Ski House opened officially on January 1, 1939.

Designed by Alexander Tilloch Galt Durnford of the Montreal architecture firm Fetherstonhaugh and Durnford, the house had a stone foundation, square log construction that weathered to a silvery gray, pink gables, and a black Mansard roof. The front door opened onto a ski room that sported racks for 24 sets of skis, a workbench, and a small stove for waxing. Seven bunkrooms housed 24 built-in bunks.

Additional items provided by the Molsons, including mattresses, pillows, blankets, furniture, and coal for three years—even 24 toothbrushes in their holders in the bathroom—kitted out the house. Founding member Betty Kemp Maxwell, who was studying at the École des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, had created a Penguin logo, and it was inscribed over the fireplace. A unique chandelier with ski tips projecting from a pewter center made the Penguin House extraordinary.

Nine years later, in 1948, the Red Birds built a clubhouse just a few hundred yards away, on land also donated by the Molsons. Penguins attended many weekend Red Birds parties, leading to several marriages over the years.

The Penguins’ War Effort

Despite the planning that went into its design, Penguin House did not get the start its members hoped for. Within its first year, Canada declared war on Germany and entered World War II. The club joined in the war effort as part of Operation Pied Piper, a mass evacuation plan born out of British fear of air attack from German bombers. More than 20 British refugee children aged five to 14, plus two English nannies, spent the summer of 1940 at Penguin House.

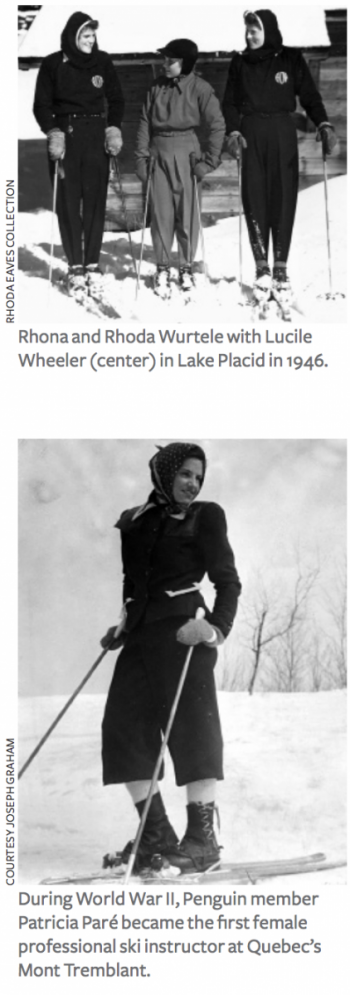

Many Penguins also joined the war effort. Seven became members of the Canadian Women’s Transport services. Others took over the jobs local men vacated to serve overseas. Penguin Patricia Paré, for example, became the first female professional ski instructor at Quebec’s Mont Tremblant.

New Directions:

The Winning Wurtele Twins

With many of its original members occupied with the war effort, the club set out to attract new interest by hosting novice races and recruiting. Among the new members were Westmount-raised identical twins Rhona and Rhoda Wurtele, who, fresh out of high school, became Penguins in 1942.

It wasn’t long before the Wurteles were winning nearly every race they entered, from Quebec to California. Rhoda won Tremblant’s Taschereau downhill by a convincing 24 seconds, beating both the women and the men. Rhona placed second among the women and ninth overall. The twins’ skiing (and swimming) talents received a lot of attention in the Canadian press. In 1947, Rhona and Rhoda were joint runners-up for the Lou Marsh Trophy, given by the Canadian Press to Canada’s Most Outstanding Athlete. All of it lent to Penguin prestige.

The Penguins and The

Winter Olympics

World War II caused the cancellation of two Olympics, but the Penguins were finally able to compete on the world stage at the 1948 Olympic Winter Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland. It didn’t go so well. The Wurtele twins were the only two members of the Canadian Women’s Alpine Team. Rhoda cracked her anklebone six days before the Games, and Rhona had an accident during her run…leaving Canada without medals.

The Penguins returned to the international arena in 1952 for the Winter Games in Oslo, Norway. Rhona was pregnant and unable to compete, but Rhoda was joined in Oslo by fellow Penguins Rosemary Schutz and Joanne Hewson, as well as Penguin Lucile Wheeler. The four competed as the first complete, four-woman alpine ski team Canada had ever sent to the Olympics.

In 1956, Wheeler was joined by Penguin Anne Heggtveit on Canada’s Olympic Alpine Ski Team at Cortina d’Ampezzo. Wheeler won a bronze in downhill, becoming both the first Penguin and the first North American to medal in the downhill. She followed this with a spectacular performance at the 1958 World Championships in Bad Gastein, Austria, where she won both the downhill and the giant slalom and came very close to winning the combined…ultimately taking the silver. She was the first North American to win a World Championship downhill. Wheeler won the Lou Marsh Trophy as Canada’s most outstanding athlete of 1958, and was later inducted into the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame and the Canadian Ski Hall of Fame, and made a member of the Order of Canada, among other honors.

Formation of the Ski Jays

Despite the Penguins’ success, the 1950s were a time when resources for Canadian skiers were extremely limited. Even while winning races and medals, the members remained true to part of the Penguin Club founding mission: “To advance the standard of ski proficiency amongst women.” Penguins Bliss Matthews and Ann Bushell hatched the idea for the Ski Jay Club in 1957 for Montreal teenage girls, envisioning the Jays as a “nonprofit organization, founded, sponsored, and at all times backed by the Penguin Ski Club.” Rhoda Wurtele was head instructor at the ski school for 21 years.

Ski Jay Nancy Holland was the first to make the Canadian ski team in 1960. Holland was joined by Penguin Anne Heggtveit. That same year, Heggtveit won Canada’s first-ever Olympic skiing gold medal in Squaw Valley, California. Her victory in the Olympic slalom event also made her the first non-European to win the FIS world championship in slalom and combined. In Canada, Heggtveit’s performance was recognized by Canada’s highest civilian honor when she was made a member of the Order of Canada. She was awarded the Lou Marsh Trophy as Canada’s outstanding athlete of 1960. These achievements were instrumental in increasing the popularity of skiing in Canada, and particularly in Quebec.

the Penguins Develop Grassroots

As the Laurentians began to thrive as a major ski destination, Penguin alumnae began spending more time recruiting and coaching new talent. Penguins Sue Boxer and Liz Dench started the Polar Bear Club in 1961 and taught four- to eight-year-olds to ski for the next 20 years. Rhona Wurtele founded the Ski Chicks in 1961 for nine- to 11-year-olds, and the Ski Jay program continued throughout these years for teens. All of these clubs groomed young girls to become Penguin members as they reached adulthood.

At least seven Ski Jays were named to the Canadian national ski team in the 1960s, including Nancy Holland, Janet Holland, Faye Pitt, Barbie Walker, Garrie Matheson, Jill Fisk and Diane Culver. With the Wurteles at the helm of the club throughout the 1970s, membership peaked at more than 1,000.

The End of an Era

In 1972, increasing costs contributed to the need to sell Penguin House. It was later destroyed by fire. Founding member Betty Kemp sang its praises: “Without the house, we wouldn’t have become and remained friends,” she said. “Without the house, we wouldn’t have had any responsibility to each other or the sport. Bonding. From the house, we learnt the responsibility of maintaining it and the club. From the club, we learnt to work together, to organize races, and to give school girls and others, the opportunity for the young to learn to ski.”

The loss of Penguin House marked the end of an era. By the early 1980s, the Penguin Ski Club had cancelled its formal incorporation. “This definitely had an impact, but we stayed positive,” says Bev Waldorf, a Penguin since 1953. Bev has remained active in the Penguins since the house closed, working with her friend Margie Knight to plan reunions, organize an annual fall luncheon and publish an occasional newsletter.

While the official club no longer exists, the spirit of the original Penguins continues. Forty-five members of the club celebrated the Penguins’ 75th anniversary in 2007, and 19 members—including five Olympians—gathered to celebrate its 85th anniversary in 2017.

This article was originally prepared for the Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame by Cara Armstrong, with subsequent research and updates by Lori Knowles and Nancy Robinson. Knowles is a Canadian writer and editor whose work appears in SNOW Magazine and the travel sections of The Toronto Sun and The Globe and Mail. Robinson served as researcher and developer for Byron Rempel’s biography of the Wurtele twins, No Limits. Special thanks to Penguin member Bev Waldorf, who vetted this article for accuracy.