Charges of sexual abuse come to light in Austria, Canada. By John Fry

The #MeToo movement has come to skiing in a swirl of proof and denial.

The #MeToo movement has come to skiing in a swirl of proof and denial.

Nicola Werdenigg—Austria’s women’s national downhill champion in 1975 when she was teenager Nicola Spiess—has charged that she was sexually molested during her years as a competitor. Though she refuses to cite names, the Tyrol State Office of Criminal Investigation is looking into the 59-year-old grandmother’s allegations.

A few months before Werdenigg’s searing confession, across the Atlantic Ocean in Quebec, a magistrate found a Canadian junior women’s ski coach guilty of 37 criminal charges related to sexual assaults on young racers in the 1990s. Nine women have publicly testified against Bertrand Charest, 52. He has been sentenced to 12 years in prison.

AUSTRIAN ACCUSERS

In November of last year, Werdernigg publicly disclosed in the newspaper Der Standard that while attending a ski academy run by a pedophile, she had been raped. She disclosed also that she had been fondled by a ski-manufacturing executive, and had witnessed abuses of other young racers.

According to Werdenigg, a second former Austrian racer has reported to Der Standard about sexual assaults in the 1970s. “We were fair game,” said the athlete, who wants to remain anonymous. “It happened to everyone. Often alcohol was involved.”

The Bavarian newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung headlined that “a climate of abuse and a culture of looking away” existed in Austrian ski racing. Former racers report serious sexual assault and rape in ski academies and on the World Cup circuit. Even the name of the iconic Austrian ski hero Toni Sailer, Olympic triple gold medalist and head coach of the Austrian national team in the 1970s, has been dragged into the scandal.

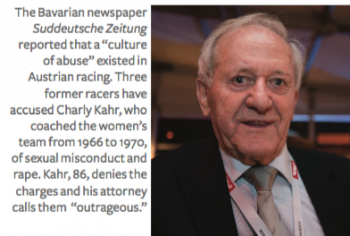

Among the Austrian coaches was the legendary Charly Kahr, who coached the women’s team in the period 1966–1970. Three former racers have accused Kahr of sexual misconduct and rape. Kahr, 86, has denied the charges. His attorney says the allegations “are pulled out of thin air…it’s outrageous now, after 50 years, to drag Charly Kahr through the dirt.” The Austrian Ski Federation, Österreichischer Skiverband (ÖSV), says it has no knowledge of the accusations.

National Ski Associations Shamed

The disclosures have proven deeply embarrassing to national ski associations. Alpine Canada “failed” its racers, admits board chair Martha Hall Findlay. “We are profoundly sorry.”

In Austria, the powerful ÖSV was criticized for insensitivity when it declared itself unable to investigate Werdenigg’s claims unless she provides names and details. “It is not appropriate to issue ultimatums,” said Defense and Sports Minister Hans Peter Doskozil. “If someone (Werdenigg) comes out and dares to take this step at personal risk, then we should expect sensitivity in dealing with the person concerned.”

Werdenigg says that it was not her intention to publicly pillory the perpetrators, but to reveal what happened so that young people will have the strength to provide information in case it happens to them.

Influence of Ski Companies

Werdenigg’s case has been intensely covered in German-language European newspapers and magazines, and she’s been interviewed on television. She stated that when she was 16 two men got her drunk, and a teammate then raped her. “I did not talk to anyone about it because I was so ashamed,” she says.

In the Der Standard interview, Werdenigg recalls being touched inappropriately by a ski-manufacturing executive. “An unappetizing old man, he asked me to sit on his knees and touched me as it should not have been. He said he needed racers like me on his team. I got up and left.”

Ski companies strongly influenced decision-making in the sport. In the 1970s, for the first time, financial contracts were at stake. Racers and trainers were rewarded for their actions.

Vonn, Moser-Proell: Differing Reactions

“The time has arrived for women to stand up,” said American downhill superstar Lindsey Vonn in reference to sexual crimes against young U.S. gymnasts. At a World Cup race at Cortina in February, according to Andrew Dempf on Therepulic.com, Vonn said, “Thankfully I haven’t experienced any of that in ski racing,” adding, “this is an opportunity for us to change how women are treated in the world.”

Annemarie Moser-Proell, whose number of World Cup wins is second only to Vonn’s among women racers, appeared unsympathetic. Proell was a teammate of Werdenigg. “When I was racing, nothing like this happened,” she said in a televised interview. “I would have been able to defend myself.

“It’s not unusual for racers on the team to become couples,” continued Proell. “It happened with Rosi Mittermaier and Christian Neureuther, and Marlies Schild and Benny Reich. There was no rape. There are always two.”

Proell expressed sorrow for coaches, supervisors and service people “who have given everything and are now put in a bad light.” Unsurprisingly, she received a verbal lashing in the social media. But she was supported by Alois Bumberger, who coached Nicola Spiess in the late 1970s. Bumberger said he was surprised by the allegations made by his former racer. He is quoted as saying that he heard nothing about sexual assaults, and no racer had ever spoken up.

She Grew Up in a Skiing Family

N icola’s parents ran the ski school at the west Tyrolean ski resort of Mayrhofen, which at one time employed 170 instructors, and had a top-notch kindergarten. Her mother, Erika “Riki” Mahringer, won two bronze medals at the 1948 Winter Olympics at St. Moritz, and two silver medals at the 1950 FIS World Championships in Aspen. Her father, Ernst Spiess, coached national team women, and was race director at the 1964 and 1976 Olympics in Innsbruck. Her brother, Uli Spiess, won two World Cup downhills.

icola’s parents ran the ski school at the west Tyrolean ski resort of Mayrhofen, which at one time employed 170 instructors, and had a top-notch kindergarten. Her mother, Erika “Riki” Mahringer, won two bronze medals at the 1948 Winter Olympics at St. Moritz, and two silver medals at the 1950 FIS World Championships in Aspen. Her father, Ernst Spiess, coached national team women, and was race director at the 1964 and 1976 Olympics in Innsbruck. Her brother, Uli Spiess, won two World Cup downhills.

Nicola herself was a prodigy. At the age of 16 she already was on the Austrian national team, registering four World Cup podium appearances her first season. She missed by 0.21 seconds a medal in the 1976 Olympic downhill, edged out by America’s Cindy Nelson, who won the bronze.

Werdennig retired from ski racing in 1981 and joined the family ski school, which no longer exists. She married Erwin Werdenigg in 1984, and has a son and two daughters. She lives in Vienna.

She suffered from an eating disorder. “There were many female racers who had severe bulimia. I was one of them. I see it in the context of the self-image that we women skiers developed under the sexist abuse of power.

“Yes,” said Werdenigg, “maybe I should have turned my back on the ski circuit earlier. But don’t forget our great emotional dependence on the sport…the sport for which one lives, for which one makes everything, for which one makes sacrifices.

“Today I am a grandmother, I have everything behind me, it’s finished, I’m not angry anymore.”

Toni Sailer Redux

The #MeToo movement recently led Der Standard to re-visit a well-known scandal that happened about the same time that Spiess-Werdennig was molested. The newspaper revealed how, in 1974, the Austrian government intervened to extricate from Poland the nation’s iconic champion, Olympic triple gold medalist Toni Sailer (d. 2009), after he was charged in a notorious rape case.

At the time, Sailer was the head coach of the Austrian alpine team and was in Zakopane for a World Cup race. He became entangled in a drunken episode in a hotel room with two Yugoslav ski servicemen. A part-time prostitute was violently raped. The Austrian government prevailed on Poland to get Sailer out of the country before he was jailed. Sailer claimed he was set up.

The best perspective on the entire affair comes from Austrian sports historian, Rudolf Müllner. You can read it online at https://derstandard.at/2000072416580/Das-Bild-wird-jetzt-veraendert-das-...

Canadian coach jailed

Between 1991 and 1998, Bertrand Charest coached the Canadian national junior ski team, the Quebec Ski Team, Team Laurentians and the Mont-Tremblant Ski Club. He was originally arrested in 2015 for sexual assault and exploitation of young racers, and has already served five years of a 12-year sentence. Charest is appealing the sentence. He denies the allegations, but remains in prison.

Last June, in a packed courtroom in St. Jerome in the foothills of the Laurentian Mountains north of Montreal, Quebec court Judge Sylvain Lépine described Charest as a “predator” who had total control over the girls and young women he was coaching. Nine of them, who were between 12 and 18 years old at the time of their molestation, came forward to testify.

According to the Star.com, which covered the trial in St. Jerome, one former Canadian ski racer testified that Charest took her to have an abortion when she was about 15. She’d become pregnant after having unprotected sex with him on numerous occasions. The woman, whose identity is under publication ban like the other witnesses, recalled that she was young and in love with her coach, and that Charest advised her to keep their relationship quiet because he would go to prison if it became known.

Judge Lépine said the victims were vulnerable and compromised because they were afraid to lose Charest as a coach. The judge said that Alpine Canada had failed to protect its athletes, and that the organization chose to close its eyes to what the athletes were saying about Charest.

Canadian Ski Federation Apologizes

In a statement, Alpine Canada board chair Martha Hall Findlay said, “Today, after a long and very difficult time for the victims and families, Bertrand Charest was sentenced to 12 years in prison, for things that he did over 20 years ago.

“At the time, Alpine Canada—instead of being there for the athletes, instead of providing support when these activities were discovered—put itself first, not the victims. In doing so, Alpine Canada failed them.” Findlay said Alpine Canada has changed its policies and procedures to prevent similar situations from occurring in the future.

The #MeToo movement is not believed to have generated any actions against the U.S. Ski Team. The nonprofit organization SafeSport, created last year and based in Denver, offers athletes and trainers the opportunity to report a concern or a violation, and to research past disciplinary decisions.

John Fry is the author of The Story of Modern Skiing, about the revolution in equipment, technique, resorts, Olympics, media and environment that transformed the sport after World War II.