From Turkey to Turin, the Occasionally Murky History of Snowboarding’s First 400 Years

By Paul J. MacArthur

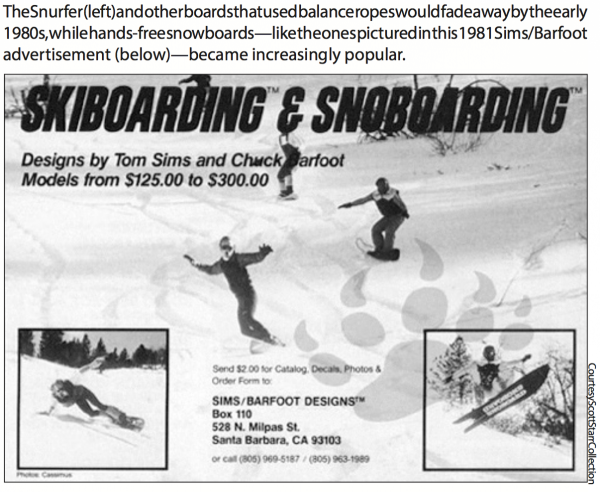

The origins of snowboarding are poorly documented. Conceived and promoted by hobbyists, the exact beginnings and history of the sport are often disputed as some pioneers try to position themselves in the history books. As Chuck Barfoot, who started building boards in the 1970s, notes, “The dates keep getting pushed back.”

When the first person rode a single plank through the snow is unknown, but anecdotes of miners in Austria riding a long wooden board with a rope or handlebar for balance—the device was called a ruariser knappenroesser (nicknamed the knappenross)—date back to the 16th century, and there are tales of a knappenross race taking place in the 1800s. Another invention called the ritprätt (also called the rittpritt), on which a rider could sit or stand, is supposed to have been used in the Swiss Alps during a similar timeframe. Austrian Toni Lenhardt is believed to have ridden a monogleider (which translates to “monoslider”) in 1900. It’s said Lenhardt used his invention in the Alps and held a monogleider contest in 1914 in Bruck an der Mur. Whether knappenross, ritprätt, or monogleider riders rode their boards like snowboards or monoskis is still being researched.

There are also claims that U.S. soldiers stood sideways on barrel staves and slid downhill during World War I. A number of snowboard history Websites mention M. J. “Jack” Burchett, who supposedly took a piece of plywood or a barrel stave, secured his feet with clothesline and horse reins, and sailed through the snow in 1929. Who was Burchett and where did he live? No one knows. The source of the story was the grandfather of a friend of a guy who worked at Transworld Snowboarding. There’s also the tale of someone in Finland snowboarding in 1932, and the list goes on.

There are also claims that U.S. soldiers stood sideways on barrel staves and slid downhill during World War I. A number of snowboard history Websites mention M. J. “Jack” Burchett, who supposedly took a piece of plywood or a barrel stave, secured his feet with clothesline and horse reins, and sailed through the snow in 1929. Who was Burchett and where did he live? No one knows. The source of the story was the grandfather of a friend of a guy who worked at Transworld Snowboarding. There’s also the tale of someone in Finland snowboarding in 1932, and the list goes on.

Many of these stories are just considered part of snowboarding’s disputed folklore. Until recently, Western snowboard historians were apparently unaware of any community that was actively riding snowboard-like devices when snowboarding’s modern era began in the 1960s. Then, in January 2008, while working on the O’Neill film Legends, snowboarders Jeremy Jones and Stefan Gimpl journeyed to Turkey’s Kaçkar Mountains and were introduced to people in a remote village who ride sideways on a flat, rectangular, toboggan-like device called a lazboard. The lazboard has a balance rope attached near the front and the rider holds a stick with the rear hand to assist in steering. According to legend, the practice began some 400 years ago for fun and it made traveling in deep snow easier. Ninety percent of the town rides and no one has ever skied. Based on current research, this community—which had been featured on Turkish television before the O’Neill crew was introduced to it—has been actively riding snowboard-like devices for a continuous period longer than any other population.

Curiously, the Turkish boards bear a strong resemblance to a controversial “sled” patented in 1939 by Gunnar and Harvey Burgeson and Vern Wicklund. The curved sled has a grooved rubber pad, a strap for the rear foot, a rudder, and a rope on the front. Like the Turkish riders, Wicklund used a stick for steering. According to The Snowboard Journal, Wicklund created the device as a teenager circa 1917 in Cloquet, Minnesota. In the late 1930s he attempted to sell the boards, but was never able to find a financial partner and the idea was dropped by the dawn of World War II. Yet, despite being referenced in at least five 1960s single-plank patents, including the legendary Snurfer, Wicklund’s board was virtually unknown to most members of the snowboarding industry during the sport’s post-1970s explosion. Then, at the 2000 Snowsports Industry of America (SIA) Trade Show in Las Vegas, Burton Snowboards produced the original Wicklund patent, a Wicklund sled, and a film of Wicklund riding at the Nordic Hills Country Club in Oak Park, Illinois in 1939. Though Wicklund rode his “sled” into his 40s, and the board is a predecessor to the modern snowboard, there’s no evidence the invention had any influence on modern snowboarding.

After World War II, more Wicklund-like boards were patented, including O. J. Lidberg’s 1948 Glider Sled, which suggested the use of a stick for steering, and Arthur Juntunen’s 1949 Toboggan, which did not. Both incorporated balance ropes on the front. But the explosion of single-plank inventions didn’t happen until the 1960s, when several snowboard-like patents were granted. Carl E. Hagen’s 1967 Snow Board looks like a toboggan, but the front and back are turned up at sharp angles. Craig T. Christy’s 1967 Snow Surface Rider is basically a skateboard for the snow with a rudder on the bottom and blocks on the deck so riders could brace their feet. Joel Salisbury’s 1968 Snow Sled looks like a small surfboard, while John Fulsom’s toboggan-like 1968 Snow Ski Board curves upward on the front and has rudders on the bottom. James L. Rippetoe’s 1968 Slalom Snow Ski is based on a water-ski design, with the front foot facing forward and the rear foot turned at a 45-degree angle to the length of

the board. Victor T. Berta’s 1969 Snowboard has magnets to help keep boots in place and Ronald Carreiro’s 1971 Snow Surfboard bears a resemblance to a small rounded wakeboard with a braking device on the bottom. None of these devices really dented the marketplace.

One invention, however, did: Sherman Poppen’s Snurfer (see “Sherman Poppen: Snowboarding’s Godfather,” in the June 2008 issue). Poppen created the Snurfer on Christmas morning in 1965 by cross-bracing two skis together. He later attached a rope to the front and licensed the invention to Brunswick, and years later JEM. Launched in September 1966, the Snurfer was a hit as more than 750,000 were sold nationwide during the 1960s and 1970s. More than any other invention, the Snurfer inspired a generation of kids to surf the snow, including future snowboard innovators Jake Burton, Chris Sanders, Bob Weber and Jeff Grell.

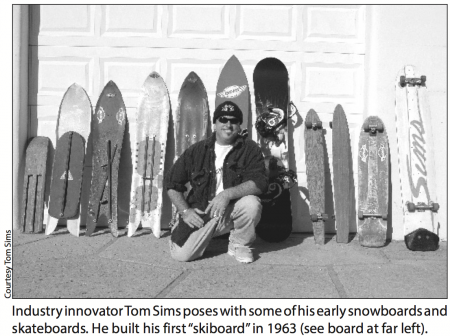

Toms Sims and the Skiboard

A New Jersey native and skateboard icon, Tom Sims is one of snowboarding’s most important figures. His snowboard company was one of the industry’s top brands from the late 1970s through the mid 1990s, and he was one of the sport’s first stars. Sims doesn’t consider Wicklund’s sled, the Snurfer or the lazboard snowboards. “When you have a rope on the front of a board, it is no longer snowboarding,” says Sims. “When you are dragging a stick for balance behind you, it is no longer snowboarding ... Snowboarding is riding a single board down a mountain with your hands free.”

Sims has claimed for decades that he invented snowboarding, though no patents bear his name. His assertion rests on the fact that in December 1963—as a skier and skateboard fanatic who was already fashioning his own skateboards—he made a three-foot piece of rectangular wood with aluminum sheeting into his first “skiboard.” The crude plank allowed him to mimic skateboarding on the snow and he continued to modify his boards throughout high school. After a brief stint at New Hampshire’s Hawthorne College, Sims moved to Santa Barbara in 1970, right before the skateboarding scene exploded. He ran a small skateboard shop and eventually morphed it into one of skateboarding’s leading manufacturers. In 1976, he was skateboarding’s world champion and co-holder of the high jump record, and was also making prototype skiboards.

In 1977, Maryland-based Bob Weber contacted Sims Skateboards, talking to both Sims and his employee, New Jersey native Chuck Barfoot. Weber had been working on his own version of the snowboard and needed a partner. He’d already trademarked the term “Skiboard” in 1975, patented his own variation of the snowboard (called a Mono-Ski) in 1975, and, according to at least one account, had been selling a different patented version of his skiboard by mail order circa 1977. Weber, Sims and Barfoot worked together to create the legendary Flying Yellow Banana Skiboard, which was launched to the public during the 1978–1979 season. The board consisted of a large plastic shell with a skate deck mounted on top. Though it wasn’t exactly what Sims envisioned, it enabled Sims and Barfoot to get a board on the market while they modified their prototype skiboards.

In 1977, Maryland-based Bob Weber contacted Sims Skateboards, talking to both Sims and his employee, New Jersey native Chuck Barfoot. Weber had been working on his own version of the snowboard and needed a partner. He’d already trademarked the term “Skiboard” in 1975, patented his own variation of the snowboard (called a Mono-Ski) in 1975, and, according to at least one account, had been selling a different patented version of his skiboard by mail order circa 1977. Weber, Sims and Barfoot worked together to create the legendary Flying Yellow Banana Skiboard, which was launched to the public during the 1978–1979 season. The board consisted of a large plastic shell with a skate deck mounted on top. Though it wasn’t exactly what Sims envisioned, it enabled Sims and Barfoot to get a board on the market while they modified their prototype skiboards.

The Flying Yellow Banana didn’t threaten the ski business and Sims quickly discovered that selling a product in a hot industry like skateboarding was considerably easier than creating a market for a new product. “I sent Chuck Barfoot and Bob Weber on a sales trip to Utah to try to sell our snowboards,” he recalls. “Chucky was excited that he got two stores to think about maybe taking some boards on consignment. That was the success of the sales trip: two stores considering putting some snowboards on consignment. That’s how tough it was.”

Dimitrije Milovich and the Winterstick

In 1970, Dimitrije Milovich read a letter to the editor concerning “snow surfing” by Bayonne, New Jersey native Wayne Stoveken in Surfing magazine. Born in Holland, Milovich grew up in White Plains, New York, and upon reading the letter, found the surfer who had been making boards since 1964. That winter, he borrowed one of Stoveken’s boards—a six-foot, 20-pound piece of redwood—and tried it out at a local ski area. “I was hooked,” he told the Deseret News in 2003. “That was the coolest thing I ever did.”

Stoveken taught Milovich how to build boards and they received two Snow Surfboard patents in 1974 that are generally considered the first modern snowboard patents. In 1972, Milovich dropped out of Cornell University and moved to Salt Lake City to enjoy the champagne powder. That winter, he was allowed to try out his prototypes at Snowbird and made ends meet by handing out towels at the resort’s sauna. Stoveken would follow in 1974 and the two opened a shop in Salt Lake, where they built and sold a few boards. They called them Wintersticks.

Wintersticks had foot straps, leashes and no rope. Milovich was the first snowboard maker to use fiberglass, a polyurethane foam core, a P-Tex bottom and metal edges; he quickly discarded the latter, as they served no purpose in Utah powder. The early Wintersticks received national attention in SKI in 1974 and Newsweek in 1975. “Dimitrije probably was the first to actually build a rideable modern snowboard,” says Sims. “When he marketed those, that really raised eyebrows. [It proved] that snowboarding was much more than Snurfing.”

When orders for the prototypes started to come in, Milovich formed the Winterstick Company with Don Moss and Renee Sessions during the 1975–1976 season. (Homesick for the Jersey shore, Stoveken had moved back East. He passed away in 1978 from a respiratory illness.) There were two Winterstick designs: the round tail and the swallowtail, the latter having a large split in the rear that helped it sink deep into powder and also acted like a fin for control. “They helped push things,” Burton says of Winterstick. “They had some great powder riding.”

Milovich tried to sell his Wintersticks at the SIA and NSGA shows in 1977, but potential buyers were not interested in the boards. “At the 1977 SIA Trade Show, we were sure all we had to do was show up and we would get dozens, if not hundreds of orders,” Milovich told Slug Magazine in 2002. “We had a film and posters, but of course we didn’t sell anything. We were pretty heartbroken. That was our first introduction to the market.” Nonetheless, he pressed forward and during the 1978–1979 season Wintersticks were being sold in 11 countries. By the early 1980s, the boards were a small cult phenomenon in Europe, France in particular, where Regis Roland popularized them in the classic film Apocalypse Snow.

Jake Burton Carpenter and Burton Boards

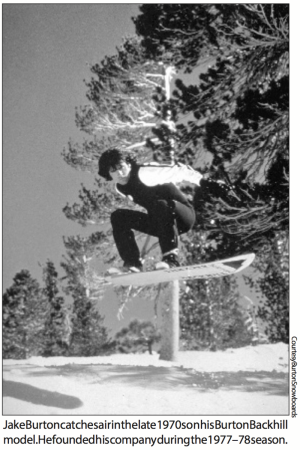

When Jake Burton Carpenter was 14, his parents bought him a Snurfer. Already a proficient skier, the Long Island teenager liked the single-plank design, the lack of uncomfortable footwear, and the board’s surfing sensation. While he was a competitive skier—he had a shot at making the University of Colorado at Boulder’s NCAA championship ski team before fracturing his collarbone in a car accident—Burton always preferred Snurfing to skiing. “You just have so much more feel,” he says. “You’re riding as opposed to skiing. That just appealed to me from the start.”

After graduating from New York University with a degree in economics in 1977, Burton worked for a mergers-and-acquisitions firm. But he had also been tinkering with different Snurfer-like devices for years and was convinced there was a viable market for them. After a falling out with his boss, Burton left the financial field behind and moved to Londonderry, Vermont during the 1977-1978 season to form Burton Boards. He brought his boards to market during the following season and sold a paltry 300 units. Having blown through a $100,000 inheritance, that summer he was back on Long Island teaching tennis during the day and tending bar at night. “That was rock bottom right there,” Burton says. “Everybody rejected (snowboarding) sort of out of hand. I visited skateboard shops, surf shops, ski shops, windsurfing shops, and nobody wanted any part of it.”

During the 1979–1980 season, Burton was back in Vermont hawking his boards. He sold 700 units and figured the 133 percent increase was a trend. “For years the company doubled its business,” Burton recalls. “Even though financially we were very much behind the eight ball, from the perspective of having confidence about what was going on, I felt a lot more positive after that.”

Several hundred other snowboard manufacturers emerged over the next two decades. Some of the notable early entrants include Washington-based Mike Olson’s GNU Snowboards, Rhode Island’s Steve Derrah, who extended his Flite skateboard operation into snowboards, California’s Jack Smith’s A-Team sand and snowboards, and Chris and Bev Sanders’ Avalanche Snowboards. Additionally, Barfoot left Sims in 1981 and formed Barfoot Snoboards.

Under-capitalized hobbyists, who lacked the business savvy necessary to succeed, ran most of the snowboard companies that materialized during the 1980s and 1990s. “We had companies that would be a guy with a press in his garage that made 100 snowboards,” laughs Lee Crane, former editor of Transworld Snowboarding. “As the industry changed and people got more serious about the business, shops realized the guy with 100 boards from the garage wasn’t going to be able to support it.” The typical snowboard company was out of business in a few years.

The first contests and stars

The first single-plank contests were the Snurfing competitions held at Block House State Park in Michigan in conjunction with the Muskegon Community College Winter Carnival during the late 1970s. “I was one of the first national champions,” says Paul Graves, who took up Snurfing as a 12-year-old while living in New Jersey in 1966. “But I like to put that in perspective. There was no true ‘national’ aspect to the sport then. It was a bunch of mostly guys, drinking a bunch of beer, getting high, hiking out in the woods, and running this course. But it was a ball.”

The first national snowboarding contest was held in April 1981 at Ski Cooper, in Leadville, Colorado. Organized by Richard Christiansen—a landlocked surf bum who ran a surf shop in Boulder and was interested in the burgeoning snowboarding scene—the King of the Mountain contest attracted a couple dozen competitors, including Burton, Sims and Jack Smith. The contest had three categories: Slalom, Freestyle (tricks and a jump) and Downhill. Scott Jacobson won the overall, with second and third place going to Sims (who took first in the slalom) and Burton respectively. Though Christiansen ran three more annual competitions at Colorado’s Berthoud Pass, the King of the Mountain event ceased operations before the sport’s real growth years.

In February 1982, Graves, who was now running the Snowboard East shop in Woodstock, Vermont, organized the first National Snowsurfing Championship at Suicide Six. 125 riders showed up, including Burton and Sims, and the contest was covered by Sports Illustrated, the Today Show, and Good Morning America as Sims captured first place in the downhill and Burton rider Doug Bouton took the slalom and the overall. After the first year, Graves asked Burton to take over the event and for the next two years he hosted it at Vermont’s now-defunct Snow Valley ski resort. (Tom Sims won the slalom, downhill and the overall at the first Snow Valley event.) In 1985, Burton moved the contest to Stratton, where it was rechristened the U.S. Open Snowboarding Championship. Sims again won the slalom. Today, the U.S. Open attracts more than 30,000 spectators and is considered snowboarding’s most prestigious event.

Not content to be a participant, Sims hosted the first World Snowboard Championships in 1983 at California’s Soda Springs Ski Bowl, where he introduced the halfpipe to competitive snowboarding. The skateboard-influenced event would usher in snowboarding’s freestyle movement and change the face of the sport, but controversy ensued when Burton’s team threatened a boycott. The halfpipe was a West Coast phenomenon at the time, and the last-minute inclusion of the event, which Burton riders had not practiced, put Burton’s team at a distinct disadvantage. The halfpipe event happened, and five years later the halfpipe became a staple at Burton’s U.S. Open. Who won the Worlds? Sims took first place in the slalom and the overall. The World Championships relocated to Breckenridge in 1986, and while it had a certain degree of cachet, particularly during the late 1980s, the event lost much of its luster during the 1990s as the Sims brand name kept changing hands.

Not content to be a participant, Sims hosted the first World Snowboard Championships in 1983 at California’s Soda Springs Ski Bowl, where he introduced the halfpipe to competitive snowboarding. The skateboard-influenced event would usher in snowboarding’s freestyle movement and change the face of the sport, but controversy ensued when Burton’s team threatened a boycott. The halfpipe was a West Coast phenomenon at the time, and the last-minute inclusion of the event, which Burton riders had not practiced, put Burton’s team at a distinct disadvantage. The halfpipe event happened, and five years later the halfpipe became a staple at Burton’s U.S. Open. Who won the Worlds? Sims took first place in the slalom and the overall. The World Championships relocated to Breckenridge in 1986, and while it had a certain degree of cachet, particularly during the late 1980s, the event lost much of its luster during the 1990s as the Sims brand name kept changing hands.

Unique among snowboard contests is the Legendary Mount Baker Banked Slalom, first held on Super Bowl Sunday in 1985. Hosted by Bob Barci, with help from Tom Sims, the race took place on “The Chute,” which has gullies that resemble halfpipes. The course gates were placed on the chute’s walls, creating considerable challenge. The atmosphere was laidback, contestants vied for pride and a small cash prize, and Tom Sims won. The Mount Baker Banked Slalom’s atmosphere, combined with its difficult course and infamous duct-tape trophy, has made it a favorite among riders. It’s also served as something of a proving ground, as many of the winners have been some of the sport’s biggest names, including Shaun Palmer, Craig Kelly, Rob Morrow, Ross Rebagliati, Terje Haakonsen and Victoria Jealouse.

“The actual events themselves seemed to stimulate innovations,” says Sims. “The contest results were a big deal in the early days and, especially from the Burton and Sims perspectives, having superior equipment was important so we could dominate at the contests.”

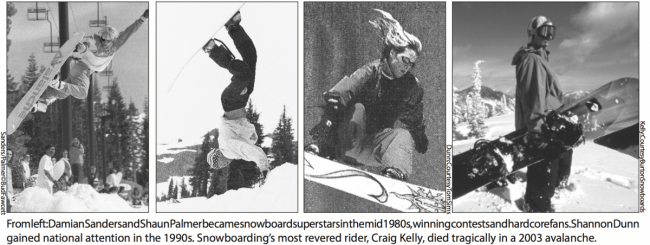

The contests also created the sport’s first superstars. Tom Sims dominated the early contests and stunt-doubled as James Bond in A View To A Kill’s opening snowboarding scene. Terry Kidwell became the “Father of Freestyle” in the early 1980s by introducing a series of tricks, including hand plants, 360s and method airs. Damian Sanders and Shaun Palmer were the wild children, looking like members of hair and punk bands respectively. They were charismatic, partied like rock stars, won contests, and quickly became heroes to the sport’s core young male demographic. Women riders really didn’t make a big impact during the mid-1980s, but Shannon Dunn and Tina Basich earned mainstream attention in the 1990s, while Michelle Taggart quietly became the most decorated female rider of the decade and British Columbia native and former ski racer Victoria Jealouse earned legendary status for her big-mountain riding in snowboarding films.

Snowboarding’s most revered rider was Craig Kelly. The somewhat reclusive Washington native was one of snowboarding’s best in the late 1980s, racked up several titles, and walked away from competitions in the early 1990s to focus on big-mountain backcountry riding, where his movie appearances made him a freeriding god. Sadly, Kelly died in an avalanche on January 20, 2003 while guiding on Tumbledown Mountain in British Columbia. Snowboarding had lost its first hero.

Banned from the resorts

When Winterstick, Burton and Sims started their companies, snowboarding was generally relegated to the backcountry. Some resorts allowed it on a case-by-case basis, but often boarders had to hike to ride in secret areas. The first halfpipe, in fact, was not discovered at a resort, but behind the Tahoe City dump in 1979 when Mark Anolik was looking for a place to snowboard.

Yet, snowboarding couldn’t grow without resort acceptance, and in the early years that acceptance proved difficult. Many ski areas claimed that snowboarding wasn’t covered under their insurance policy, though it’s been suggested that such assertions had no merit. Nonetheless, the famous Stratton mountain case, in which skier James Sunday was awarded $1.5 million in 1977 as a result of a skiing accident that left him paralyzed from the waist down, scared a number of resorts into banning everything but skis. Additionally, many resorts saw little reason to accept a few snowboarders.

Smaller resorts were often the first to allow snowboarding, in part because they needed the business. Larger resorts were a more difficult sell as they didn’t want to annoy their skiing constituency. Snowboarders ride the mountain differently and that irritated skiers. Additionally, snowboarding appealed to teenagers who acted like, well, teenagers. They ducked lift lines, made counterfeit lift tickets, went out of bounds (the early boards didn’t work well on hardpack), and got drunk and high in the woods. In other words, they were just like the ski bums of decades past. But snowboards marked them as skier enemies.

Regardless, money talked. According to the National Ski Areas Association, between the 1978–79 and 1984–85 seasons, industry-wide skier visit totals grew by only 2.3 percent. With skier visits relatively flat, and snowboarding growing slowly but consistently, the writing was on the halfpipe wall. Despite being dubbed the “Worst New Sport” of 1987 by Parade magazine, resorts accepted snowboarding’s overtures, thanks in part to the diplomacy of Burton’s Paul Alden and Avalanche’s Bev Sanders. According to the United States Ski Industry Association, approximately 40 resorts allowed snowboarding during the 1984–1985 season. By 1990, that number had increased to 476.

Burton booms while other firms founder

During the 1980s, several snowboarding companies started to run into financial problems. Winterstick closed in 1982, re-launched in 1985 and closed again in 1987, just before snowboarding started to experience exponential growth. The Winterstick trademark, abandoned by Milovich in 1983, was subsequently resurrected by another company with no involvement from Milovich.

Most of the other early movers didn’t fare much better. A-Team and Flite perished. Avalanche was sold and is a niche brand. Barfoot closed up the snowboarding side of his business, though he’s now producing a small run of handmade snowboards available via mail order. In 1986, Sims began licensing out his snowboard business, but the deals (all four of them) proved problematic and hurt his ability to deliver product and react to market changes. Today, he licenses his name to Collective Licensing, which distributes Sims snowboards and skateboards to Sports Authority. Burton aside, Olson’s GNU is the most successful of the early entrants, though GNU and sister brand Lib Tech were acquired by action sports company Quicksilver in 1997.

While several manufacturers were plagued with problems, Burton was not. The consummate businessman, Burton skillfully navigated the snowboarding business terrain. When Rossignol’s Vermont division had financial problems, he hired several of their top people and built a solid management team. Burton wasn’t high on team competitions, but when he realized competition was an important part of snowboarding, he embraced it. Freestyle and halfpipe riding didn’t interest him, but when he saw that was where the sport was headed, he signed freestyle champion Craig Kelly away from Sims. He also poached Shannon Dunn from Sims and pillaged the Barfoot team for top riders.

Burton penetrated the European market in the mid-1980s and struck a deal with an Austrian manufacturer, which allowed him to produce boards more cheaply. He obtained financing through capital investment from his wife’s family and some private bank loans, which provided him the liquidity necessary to produce enough product for the burgeoning late-1980s market. Meanwhile, his competitors were back-

ordered. No snowboard manufacturer had Burton’s combination of business prowess and capital, and the ski companies weren’t interested. “I almost literally lost sleep over the fact that somebody like Rossignol was going to start making snowboards and that was going to be the end of me,” says Burton. “But it’s incredible that they all gave me a ten-year head start. I had ten years of business before any of those guys got involved, which gave me and gave Burton an opportunity to establish an industry and a company and get fairly well capitalized and organized.” Why didn’t the ski industry jump on the bandwagon? Lack of foresight, says Chuck Barfoot. “Basically, the ski companies were laughing at us,” he told the Santa Barbara Independent newspaper in 2008. “Little did they know what snowboarding would become.”

Snowboarding goes gold in the 1990s

With the vast majority of resorts now accepting snowboarding, the sport experienced rapid growth during the 1990s. According to the National Sporting Goods Association, the number of riders rose from 1.5 million to 4.3 million between 1990 and 2000, while the number of skiers dropped by 4 million. Snowboarding was often tagged as the fastest-growing sport in the U.S., Jake Burton appeared in an American Express commercial, and ESPN brought more attention to the sport with Snowboarder TV and later the Winter X Games. The sport’s image also became even more rebellious and a bit darker as teenage participants embraced the grunge scene. Since 1990, the 12- to 24-year-old age group has accounted for 75 to 80 percent of the sport’s market, and snowboarding’s image has consistently reflected this group.

The industry’s growth resulted in Burton’s nightmare materializing as Rossignol, Salomon, Volant, Atomic and K2 all started snowboard production during the late 1980s and early 1990s. But most of the ski companies, with the exception of K2, were too late to the dance. Their brands lacked authenticity and couldn’t damage Burton’s position. They did, however, have enough capital to take significant market share away from the smaller companies and further entrenched Burton as the market leader.

The industry’s growth resulted in Burton’s nightmare materializing as Rossignol, Salomon, Volant, Atomic and K2 all started snowboard production during the late 1980s and early 1990s. But most of the ski companies, with the exception of K2, were too late to the dance. Their brands lacked authenticity and couldn’t damage Burton’s position. They did, however, have enough capital to take significant market share away from the smaller companies and further entrenched Burton as the market leader.

Meanwhile, the International Olympic Committee took notice of the sport’s popularity and youth appeal. The IOC wanted snowboarding at the 1998 Winter Olympics, but there was a problem. The international governing body for snowboarding competitions was the International Snowboarding Federation (ISF), which had risen from the ashes of the National Association of Professional Snowboarders in the early 1990s. When the IOC decided it wanted snowboarding, the International Ski Federation (FIS) resisted, as snowboarding was considered a threat to skiing. To appease the FIS, the IOC gave it administrative power over Olympic snowboarding and the ISF was left outside. The move infuriated the snowboarding community. After being treated like an unwanted child by the ski industry for nearly two decades, competitive snowboarders now had to deal with the FIS if they wanted to compete in the Winter Olympics. Jake Burton, by now the most influential person in the business, said he was never even contacted about the 1998 Winter Olympics and years later, Shannon Dunn would reveal that the U.S. Olympic team coaches didn’t really snowboard.

When snowboarding debuted at the Winter Olympics in Nagano, the riders appeared to have the last laugh. Norway’s Terje Haakonsen, regarded as the best snowboarder on the planet, refused to participate. Dunn and Cara Beth-Burnside refused to wear their U.S. Olympic uniforms at a breakfast in the Olympic village. Canadian Ross Regabliati won snowboarding’s first Olympic gold medal in the giant slalom, only to have it stripped because a drug test revealed marijuana in his system. The decision was overturned (marijuana is not considered a performance-enhancing drug), but the incident reinforced the perception of snowboarders as cultural outcasts.

The 2002 Winter Olympics, however, demonstrated why the IOC coveted the sport. Crowds swelled to 30,000 in Park City with nearly a third of all U.S. households watching at least one snowboarding event. U.S. medalists made the late-night talk-show circuit and Jake Burton gave the Today Show’s Katie Couric a snowboarding lesson on TV. The success of the U.S. team further popularized the sport in the U.S. and participation levels soon rivaled alpine skiing. Four years after Park City’s success, in the ultimate case of irony, skier Bode Miller was the Olympic bad boy who partied too hard and came up empty-handed while snowboarder Shaun White dazzled audiences as he captured halfpipe gold, became the hero of the Games, and made the cover of the Rolling Stone. γ

————————————————————————

The author would like to thank Scott Starr for providing confirmation of some historical dates, John Allen, John Fry, and Marlies Fry for their helping to uncover information about the knappenross, and especially Colin Whyte for his comments and suggestions on this article.